Tea and Company: Interactions Between the Arab Elite and the British in Cosmopolitan Singapore

July 29, 2022

The Islamic New Year, also known as the Arabic New Year, falls on July 29 in 2022. It marks the first day of Muharram, the first month in the Islamic calendar.

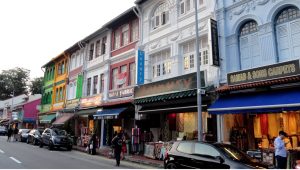

In the twentieth century, the wealthy upper strata of the Arab community, known as the Arab elite in colonial Singapore, socialised considerably with the British colonial officers. The Arabs formed the wealthiest community in Singapore, despite there being only 2,500 Arabs in Singapore and constituting less than one per cent of the population. At one point, before the outbreak of the Second World War, they owned 75 per cent of the land not owned by the British, equating to 50 per cent of the total land area in Singapore. Those who wished to acquire land in Singapore had to obtain tenure from the Arabs, as they were the legal owners of the land.

In ‘Tea and Company: Interactions Between the Arab Elite and the British in Cosmopolitan Singapore’ from The Hadhrami Diaspora in Southeast Asia: Identity Maintenance or Assimilation? (2009), Assistant Professor Nurfadzilah Yahaya (NUS Department of History) writes about how in the early twentieth century, the desire of the Arab elite to be near the British in cosmopolitan Singapore ironically facilitated British surveillance of the community as they became highly visible to the colonial government. The interactions between the Arab elite and the British through education, business activities, and informal political discussions managed to allay British fears of anti-colonial Arab movements amongst the Arabs in Singapore. In turn, this allowed the British to convey their positive intentions, while the Arabs granted themselves the opportunity to display hospitality for the British.

Social relations between the Arabs and the British in Singapore often directly hinged upon political affairs in Hadhramaut, the land of origin of the majority of the Arabs in Singapore. In this way, the continued classification of the Arabs as a distinct community that is separate from the native Malays could have been reinforced by their function as British allies in controlling Hadhramaut, which was within the British sphere of influence.

Having invested so much in Singapore, financial interests served as a strong motivation for the Arabs to maintain warm and cordial relations with the British. Members of the wealthy Arab elite in Singapore who socialised with the British and other Europeans were also markedly different from other less financially able Arabs, in that they were generally well-travelled and well-connected, and were exposed to different influences would shape their worldview differently. By leading a cosmopolitan lifestyle along with the colonial ruling elite, the Arab elite in Singapore blurred the line between the worldly coloniser and the colonised population.

Furthermore, contact between the British and the Arabs in Singapore was not purely social in nature, as the Arabs were also recognised as having important political roles within the colony. They affirmed Muslim loyalty to the British, dousing colonial fears of widespread Pan-Islamism in Singapore amongst the Muslim population.

Read the chapter here.