The Burdens of Ethnicity: Chinese Communities in Singapore and Their Relations with China

December 29, 2022

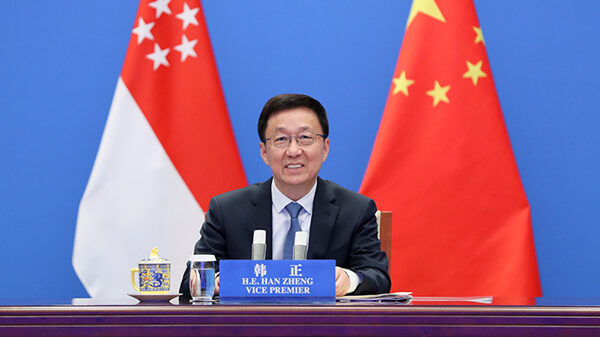

On 29th December 2021, Chinese Vice Premier Han Zheng met with Singaporean Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat, pledging to jointly fight the COVID-19 pandemic and enhance bilateral cooperation. According to Han, as close neighbours and partners, China and Singapore enjoy mutual political understanding and trust.

China is Singapore’s largest trading partner, while Singapore is the largest foreign investor in China. To seize market and investment opportunities in China, Singaporean Chinese often leverage their cultural, linguistic, and other similarities with the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s population. In this sense, Singaporean Chinese act in ways that parallel their counterparts from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and elsewhere; and may, over time, blur the distinction between the ethnic Chinese communities of Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan in China.

In ‘The Burdens of Ethnicity: Chinese Communities in Singapore and Their Relations with China’ (from Navigating Differences: Integration in Singapore (2020)), Associate Professor Ja Ian Chong (NUS Department of Political Science) writes about the complex relationship Singaporean Chinese have with China. As China develops its role as a major global actor and Singapore opens itself up to large-scale immigration, these tensions, originating from historical links between China and Singapore, the ethnic diversity within Singapore, suspicions of political influence, and more, will have to be carefully dealt with.

While the PRC is built on the idea that the Chinese national state is historically synonymous with and represents all Chinese persons living all around the world, this concept is not one that Singapore, despite having a majority ethnic Chinese population, necessarily aligns itself with. Even though the Chinese in Singapore share cultural and linguistic similarities with the communities from which they originated, their experiences and sensitivities diverge substantially from those of PRC nationals today. For instance, Chinese communities in Singapore did not have to go through events like the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, the struggles of the reform era, demands for national unification, and more. Instead, Singaporean Chinese shared more popular culture and interactions with Sinophone societies in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Malaysia.

Furthermore, PRC officials and people who grew up under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) tend to hold implicit beliefs about the universality of Chinese struggle against Western imperialism. This anti-imperialist struggle shapes Chinese nationalism and is believed by many people from the PRC to be a globally shared Chinese experience, given the way nationalist sentiments permeate the education system and popular culture in China. However, such understandings are distant, if not alien, to most Singaporean Chinese, creating friction during interactions and efforts to integrate new PRC immigrants.

Adding to concerns about relations with China and its ties with local Chinese communities is the fact that such connections can have direct implications for Singapore’s foreign affairs. Singapore’s immediate neighbours, Malaysia and Indonesia, both have histories of strong anti-Chinese sentiment, which resulted in communal violence on several occasions.

Ethnic Chinese communities in Singapore can have fruitful relationships with China, provided that there is sufficient mindfulness to mitigate the associated risks. This can be done through cooperative commercial and cultural exchanges, which can benefit both sides.

Read the chapter here.