Exploring the Early Printing Press: EN5241 Students Take Rare Books Tour of the National Library of Singapore (NLS)

December 16, 2024

By Timothy Wan (Literature MA-by-research student)

As research students in EN5241: Literature and New Worlds, 1590-1700, we studied British and Anglophone texts from the early modern period. This was a period when a variety of technological advancements made the world increasingly, and rather suddenly, interconnected, while also opening new scientific ‘worlds’ via optical instruments (from the microscopic to the cosmic). “Encounter” is a major concern in literature of the period, especially in travel writing, a massively popular genre, and the many fictional voyages based on that body of work. Across our term, we asked questions such as: Why were people interested in writing about new or distant locales? How and why did these writers represent other peoples, cultures, and countries, particularly before England’s colonial expansion? How do they describe novelty or difference? And how do their textual networks anticipate today’s globalized world?

As part of this course, we visited the Rare Materials Collection at the National Library of Singapore (NLS), where librarian Janice Loo led us on an extensive tour of the special collections area (located on the 13th floor of the NLS). After having explored written texts in the classroom, it was exciting to see first-hand some of the earliest printed texts about the region and to examine them in a different context: the fluid, international, multilingual networks of Southeast Asia.

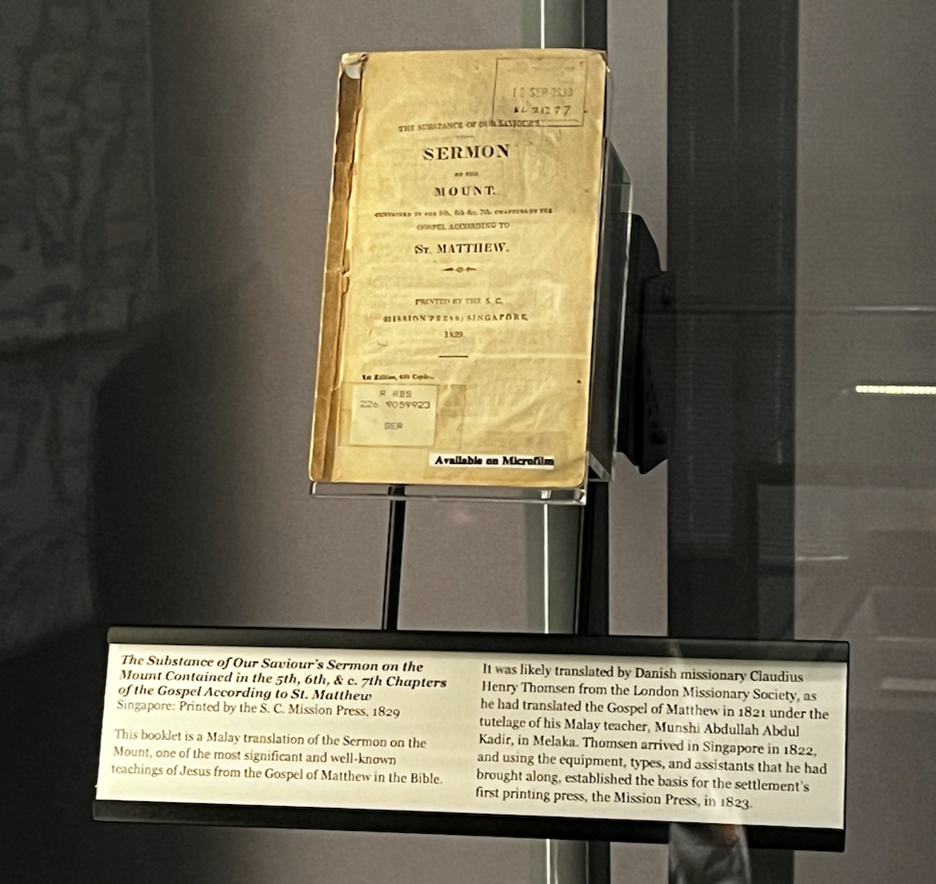

Specifically, we learned about early print networks in Southeast Asia and about how local printing presses were first set up in Singapore. We learned that much of Singapore’s early printing efforts were driven by missionaries seeking to reach local communities. The first printing press in Singapore was established by missionaries in 1823; for instance, the library’s early printed materials include a Malay translation of the Sermon on the Mount by Danish missionary Claudius Henry Thomson in 1829. This attempt to bridge linguistic gaps through translation did not initially bear much fruit. Missionaries handed booklets to local fishermen, many of whom were illiterate. However, locals still ascribed some value to these texts, which were often resold in the marketplace.

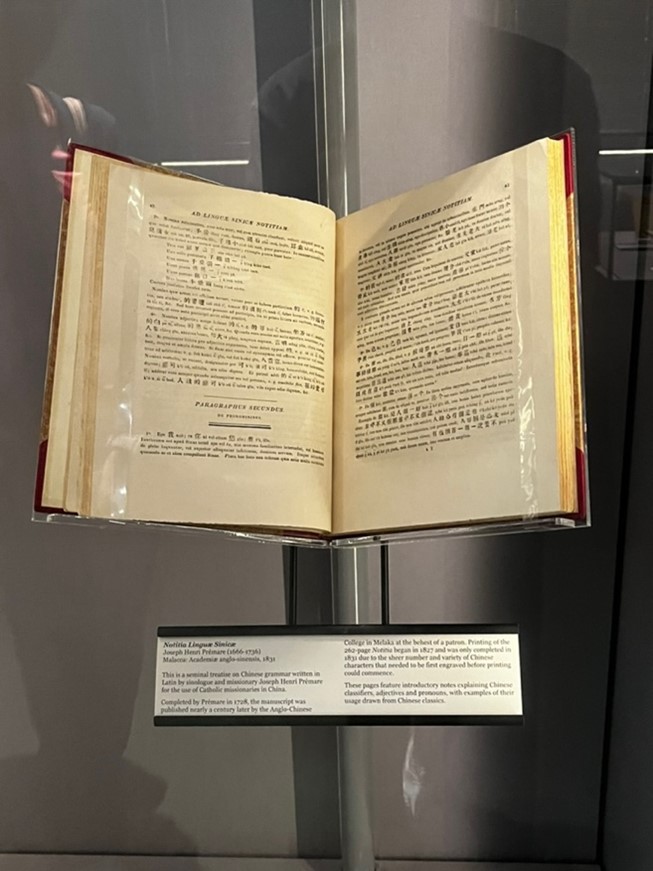

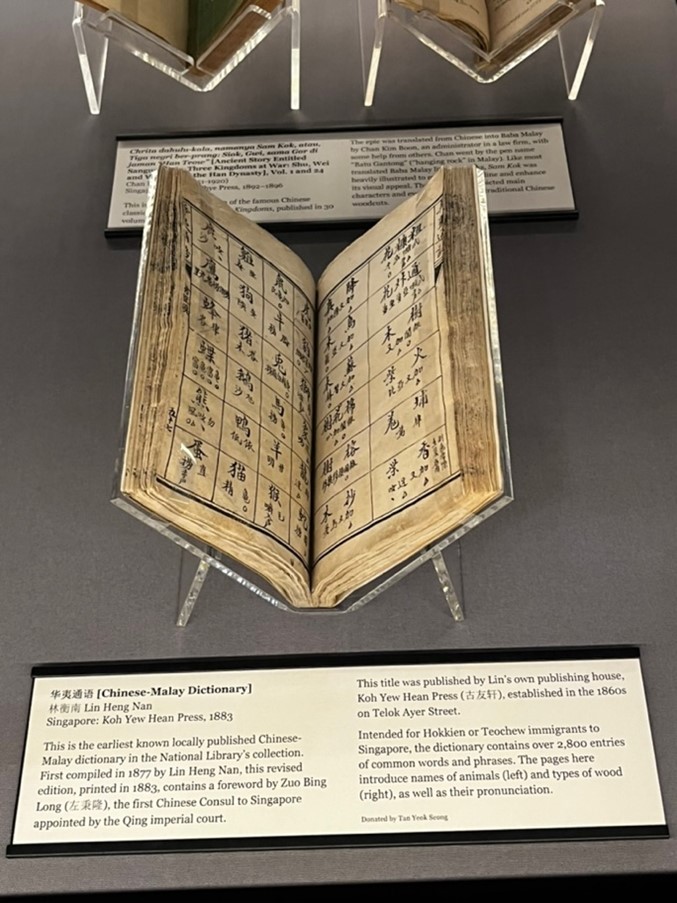

It was fascinating to see early travel writers both trying to understand the region and making it comprehensible to their readers at home. Among the artefacts we saw was an early travel account by Walter Henry Medhurst detailing his journey from Batavia to Bali in 1829. Other highlights included a treatise on Chinese grammar by Joseph Henri Prémare in 1831 and Lin Heng Nan’s 1883 Chinese-Malay Dictionary, intended for Hokkien and Teochew immigrants to Singapore. These dictionaries reflected both the literary conventions of the time and their readership-the former was written in Latin, while the latter used Chinese characters that, when read aloud, sounded like Malay words.

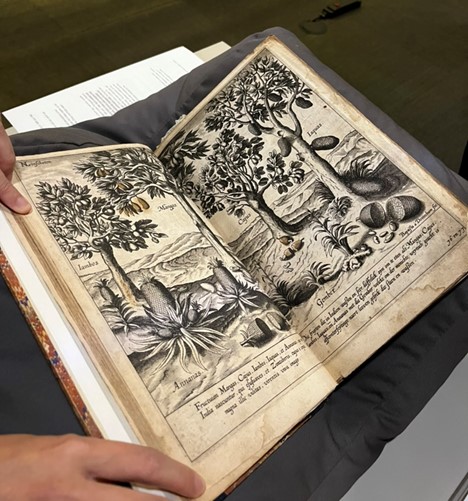

Most exciting, though, was the fact that Janice had prepared for our visit by taking out a variety of rare British texts-published from 1700 to 1780-that overlapped with the authors we studied in our class. These are usually not available to view and so it was a unique opportunity to examine them up close, page through them (carefully, with Janice’s help!), and wonder at the printing methods and elaborate, bi-colour illustrations.

The visit also invited reflection on the materiality of texts, helping us think about the historical contexts in which they were written. Working with digital copies as we often do, it is easy to forget the material conditions that determined how readers engaged with these works. Viewing old newspapers like The Straits Chinese Magazine and The Government Gazette, as well as much older historical journals, evoked thoughts about the vital social roles these texts played in their societies. Observing the wear, design, and preservation of these texts was both humbling and illuminating, evoking thoughts of the many hands through which they passed.

Overall, the tour helped us explore class questions in a more tangible way. Texts are not ‘flat’; they are shaped by those people who produce, read, and engage with them. In complementing our study of English writers, the visit revealed Singapore’s fascinating literary and printing history, deepening our appreciation for the cultural exchanges embedded within these texts and within our region.