Macroeonomic Research: Jordan Roulleau-Pasdeloup

|

Jordan Roulleau-Pasdeloup is an Assistant Professor at the Economics Department. He joined the Department in 2017, having obtained his PhD from the Paris School of Economics and after a stint as a postdoctoral fellow in HEC Lausanne. In this article, Jordan tells us about his research in macroeconomics. More information on Jordan’s research can be found on his personal website. |

I started doing research in economics in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008. Motivated by these events, my PhD dissertation focused on the effectiveness of macroeconomic stabilization policies. The main theme was to find an answer to the following question: how can/should we set monetary and fiscal policies so as to limit the increase in unemployment in a recession? In addition, through which mechanisms do these policies operate?

Understanding how these policies work can be tricky. Say we want to know the effect on unemployment when the Central Bank increases its interest rate. To get a definitive answer, one would have to mimic what is typically done in clinical trials: the policy should be enacted randomly and some households/firms should be affected by the policy (treatment group) and some others not affected at all (control group). Of course, that is not possible since policies are not enacted randomly and households/firms all interact with one another.

To deal with this issue, economists have been working with macroeconomic models. These are basically stylized representations of how an economy behaves. One can then simulate policies of interest in this model economy and then study (1) whether the policy in consideration does a good job in dampening the recession and, if yes, (2) the mechanisms through which this is achieved. Using this approach, I have focused on two policies in particular.

The first one is public investment in infrastructure. While this is a widely-debated topic, there was surprisingly little formal modelling of its macroeconomic impact. Most of the theoretical and empirical work had been devoted to military expenses because these are easier to identify in the data as being independent of the cycle and simpler to include in a model. What I have found in work with co-authors is that public investment is a very good tool to fight recessions. More specifically, compared to military spending, public investment has a higher short run multiplier effect on GDP. It also has the effect of increasing growth in the long run because the benefits of higher quality infrastructure persists far into the future. These findings based on a model economy are broadly consistent with what the empirical literature has found and can thus highlight the mechanisms underpinning these empirical results.

The other policy that I have studied using macroeconomic models is called forward guidance. This term describes a policy whereby central banks make explicit announcements for their future policy decisions. This is especially relevant nowadays since most central banks cannot decrease their interest rates too much below zero. For example, the Federal Reserve Board in the United States announced during the Great Recession that it would keep its interest rate fixed at zero for as long as necessary until the economy recovers. What research using macroeconomic model has highlighted is that there is always the possibility for self-fulfilling recessions to take hold: households/firms expect low growth, so they spend less and save more. This, in turn, brings about the expected recession into life. There is a burgeoning consensus among monetary macroeconomists that this is what has been happening in Japan over the last few decades. As a result, there is a growing literature devoted to understanding how these self-fulfilling recessions take hold and how to prevent them from doing so. In my research using macroeconomic models, I have found that making explicit announcements about future policy can prevent these self-fulfilling recessions from taking hold. What this suggests is that a bolder policy from the Bank of Japan could have helped to stave off a decades-long period of low growth.

|

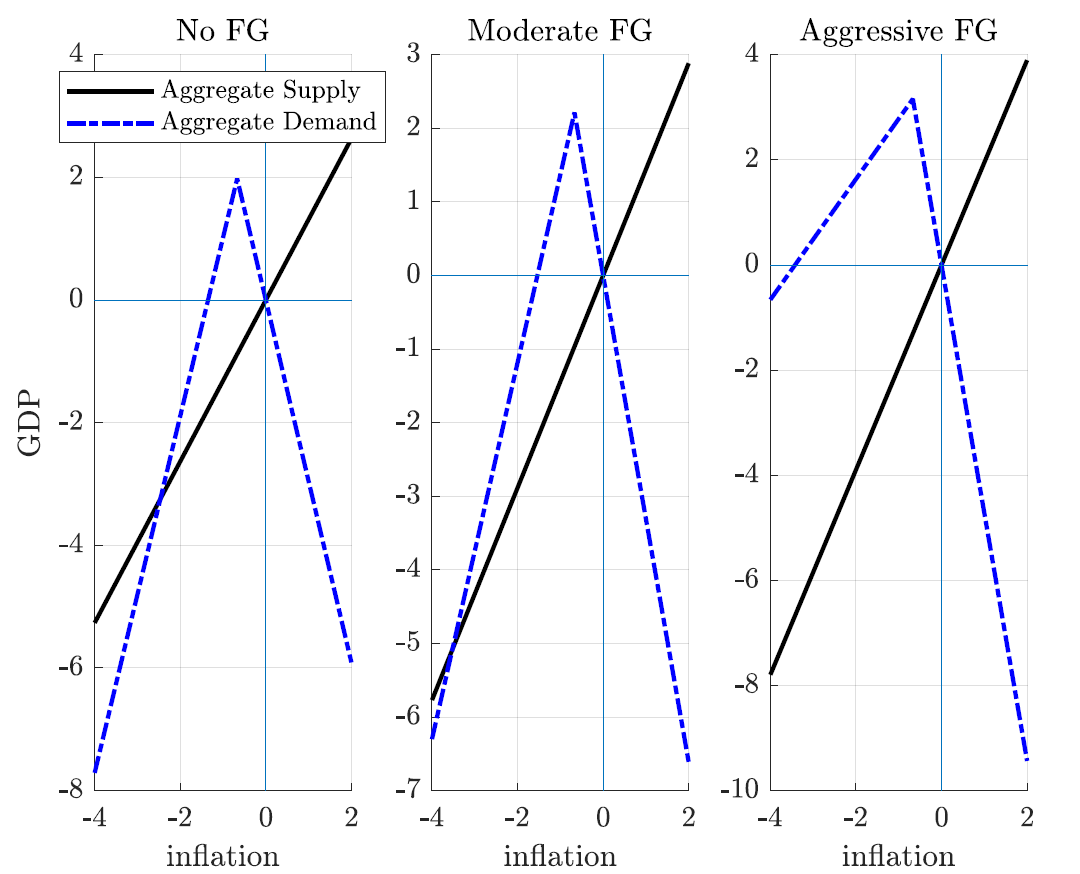

| This diagram depicts aggregate supply and aggregate demand in a typical economy. Both axes are in percentage terms. So a value of -2 on the horizontal axis means that inflation is -2% from the Central Bank target; the same for GDP on the vertical axis. When there is no forward guidance (FG), the aggregate supply and aggregate demand curves cross twice. There is one nice equilibrium where inflation and GDP deviate 0% from the central bank objective, which is what the computer simulation would focus on. But the graph shows that (in this case) there is a second, self-fulfilling equilibrium where both inflation and GDP are below the central bank's objective. The middle and right panels show that a sufficient amount of forward guidance can rid the economy of the second, self-fulfilling equilibrium. The forward guidance here is of the type provided by Jerome Powell when he was chair of the Federal Reserve Board: if there is below target inflation today, the Board will strive for above-target inflation in the medium run. In this graph, such a policy staves off a self-fulfilling recession. |

Now to be of any use, these models that we economists work with have to be considered a good enough representation of economic reality. To do so, we have to include the most relevant characteristics of an economy. In the process of doing so, the model that we end up with might become overly complicated: we have a model where household behavior depends on the behavior of firms, the government, the Central bank, and vice versa. Working with such a model entails keeping track of a very large number of feedback loops, which undermines the model’s original purpose, which is to try to understand what is happening in the economy.

In particular, the models routinely used in central banks are very complicated and feature a large number of interactions that are not well understood: one can generate quantitative answers from the model, but the actual behavior of model agents underpinning these quantitative results is not clear.

In this context, my current research focuses on devising tools that track how complicated models work. At the moment, I am focusing on models that are moderately complicated. In my latest paper, I have developed tools that enable one to exactly represent the inner workings of this model through a simple Supply/Demand graph, just like the ones that students encounter in their introductory lectures. Importantly, this graph is not the kind of ad hoc drawing that may be found in textbooks but is explicitly grounded in the complicated model that economists are working with. For example, it is very difficult to solve a model with forward guidance and one has to rely on computer simulations. Using these tools, I have managed to generate a simple representation of a model which highlights the role of a central bank in averting self-fulfilling recessions through forward guidance. In contrast, this cannot be revealed using computer simulations because the simulation would focus on the well-behaved equilibrium and would not report other equilibria that may take place. In brief, computer simulations sweep a lot of interesting mechanisms under the rug and the tools that I am developing aim to uncover these in a transparent manner.

As it stands, these tools cannot yet be applied to the kind of large models that are used in central banks and international institutions like the IMF. I am actively working with my NUS students to extend these tools so that they can be fruitfully applied to these models as well. At present, discussion of these models are mostly confined to highly-trained PhD economists in universities and central banks, even though these models are used to make important policy decisions that affect everyone. My goal is to extend the tools that I have developed so that these models become accessible to people with a basic training in economics and their findings can be more widely discussed.

Jordan Roulleau-Pasdeloup

August 2021

References

Public Investment

Public Investment, Time to Build, and the Zero Lower Bound, joint with H.Bouakez & M.Guillard, Review of Economic Dynamics, 2017, Vol 23, 60-79.

The Optimal Composition of Public Spending in a Deep Recession, joint with H.Bouakez & M.Guillard, Journal of Monetary Economics, 2020, Vol 114, 344-349.

Forward Guidance

Optimal Monetary Policy and Determinacy Under Passive/Active Regimes, European Economic Review, 2020, Vol 130, 103582.

The Promises (and Perils) of Control-Contingent Forward Guidance, joint with He Nie. Unpublished Manuscript, 2021.

Tools to understand models

Analyzing Linear Rational Expectations Models: the Method of Undetermined Markov States. Unpublished Manuscript, 2021.