SSR Snippet - March 2025 Issue 1

Understanding the Work Expectations of Youths: What Insights Can We Glean from the Sparse Academic Literature?

Leon Lim (Institute of Policy Studies, NUS), Irene Y.H. Ng and Asher Goh (Social Service Research Centre, NUS)

Keywords: low wage, young workers, work expectations, job attributes, work priorities

Introduction

Media narratives portray young workers as having high, sometimes unrealistic expectations of their jobs. These narratives are often based on market surveys or interviews with employers. For example, young workers are said to expect their employers to offer them professional and personal growth, flexibility to work from anywhere, and the option to engage in side projects outside working hours (Gogoi, 2024; Ong, 2022). However, a critical review of the academic literature reveals that there is insufficient evidence to substantiate these narratives. This is especially the case for young low-wage workers, on whom research is extremely sparse and whose expectations appear more modest and basic than suggested by the media.

We summarise some key insights from the very limited academic research on the work expectations of young workers and discuss how the expectations of low-wage young workers may differ from other young workers.

What Do Young Workers Expect?

Research across various countries indicates broad consistency in the work expectations of young workers. Key characteristics such as pay, workplace conditions, and opportunities for growth emerge as top concerns. In Singapore, for instance, Teo and Han (2023) find that individuals aged 21–35 rank pay adequacy, work conditions, and growth/learning as their three most important job attributes. Interestingly, younger respondents tend to place a higher value on growth and learning compared to their older counterparts. Meanwhile, respondents across the age spectrum rank job purpose and meaning relatively low.

A similar pattern is observed in other countries. A survey of Polish university students born after 1990 reveals that a “high salary” was the most desired job characteristic, followed closely by a “good workplace atmosphere” and “growth and self-realization possibilities” (Laskowska and Laskowski, 2021). In the UK, Grant et al. (2021) find that “good pay and conditions” top the list of priorities for youth aged 16–21; job security and a fun work environment were also emphasised.

Despite the profound changes wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, there is little evidence to suggest that there has been a significant shift in the work expectations of youths. Studies, including those by Laskowska and Laskowski (2021), indicate that the priorities of young workers have remained stable, both pre- and post-pandemic. This is probably because while young workers and low-wage workers were disproportionately affected by the pandemic, the structural forces shaping their expectations — educational attainment, socio-economic status, and the increasing precarity of low-wage work driven by digital platforms — have largely persisted (Grant et al., 2021; Miller et al., 2023; MacDonald et al., 2023).

Do We Know What Young Low-Wage Workers Expect?

Remarkably, little research has been conducted on the work expectations of low-wage youth. Existing studies are based on university-educated individuals, whose expectations and experiences are likely very different from their peers with lower educational qualifications.

There is some research on the work expectations of low-wage workers. For instance, the Worker Voices project by the U.S. Federal Reserve System (Miller et al., 2023) highlights that low-wage workers prioritize jobs with wages that cover living costs, offer respect, and allow agency in setting work-life boundaries. However, the Worker Voices project reports on low-wage workers of all ages, and did not examine how young low-wage workers may differ from their older counterparts.

At the same time, there is research addressing work expectations among youth subgroups, such as autistic youth, disabled youth, and immigrant youth. However, to the best of our knowledge, low-wage youth are underrepresented in the literature.

Indicators from the In-Work Poverty Project

Our research on “In-Work Poverty and the Challenges of Getting By Among the Young” (IWP) [1] suggests that that there are some differences in the job expectations of higher- and lower-educated young workers. In the first two waves of the surveys [2], respondents aged 21–40 were asked to identify the most important attributes in a job.

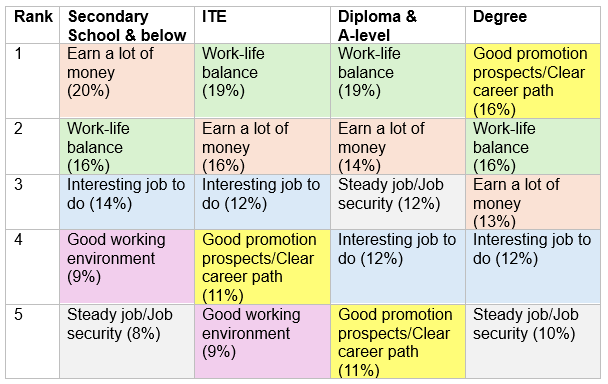

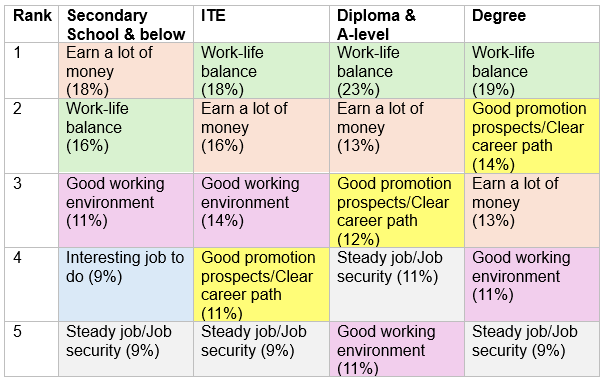

The top five choices by education level (proxying for wage levels) are in Tables 1 and 2 below, with the responses colour-coded. Many of the top five choices are similar across education levels, namely “work-life balance” (colour-coded green), “earn a lot of money” (peach) and “interesting job to do” (blue). Work-life balance was the top priority for all, ranking first or second in both waves across all education levels.

However, there are differences in the ranking of the attributes. “Earn a lot of money” was ranked most highly by respondents with no more than a secondary school education, and decreases in importance as the level of education increases. In the reverse direction, “good promotion prospects / clear career path” is ranked higher by degree holders, and is not among the top five choices for respondents with no more than a secondary school education.

The differential rankings may reflect the reality that degree holders expect to earn more than enough to cover necessities. Consequently, they prioritize career progression over high earnings. In contrast, the jobs available to the less-educated are likely to have lower wages as well as limited career progression. Hence, the less-educated young workers prioritize earning as much as possible over career progression.

Table 1: Respondents’ priorities in a job (wave 1) [3]

Table 2: Respondents’ priorities in a job (wave 2)

Concluding Thoughts

Based on our analysis of the sparse academic literature on the work expectations of young people, we caution against accepting the media portrayal of young people as the gospel truth or representative of all young workers. As our data suggests, low- and high-SES young workers have slightly different work priorities that are likely shaped by their labour market realities. Policymakers, social service practitioners, unions, and employers must recognise the diversity in the working expectations and norms of young people, and not treat young workers as a monolithic group tied to their age and generation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Tan Zhi Han and Jennifer Nguyen Ngoc Sao Chi for their research assistance.

This research is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Social Science Research Thematic Grant (MOE 2018-SSRTG-016 and MOE2022-SSRTG-028). Any opinions, findings, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Singapore Ministry of Education.

Footnotes

[1] This project was funded by the Social Science Research Thematic Grant (MOE 2018-SSRTG-016).

[2] The wave 1 data was collected from October 2020 to March 2021. The wave 2 data was collected from November 2021 to May 2022.

[3] Respondents were asked to select their top two choices. We summed up the number of choices by education level.

References

Gogoi, Shika Moni (2024). “12 Key Expectations of Gen Z Employees That Must be Addressed.” Vantage Circle. https://www.vantagecircle.com/en/blog/expectations-gen-z-employees/

Grant, Kirsteen, Valerie Egdell, and Diane Vincent (2021). “Young People’s Expectations of Work and the Readiness of the Workplace for Young People: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland. https://researchportal.northumbria.ac.uk/en/publications/young-peoples-expectations-of-work-and-the-readiness-of-the-workp

Laskowska, Agnieszka and Jan Laskowski (2021). “Expectations of Young People Towards Their Future Work and Career After the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic Outbreak in Poland.” European Research Studies Journal XXIV (Special Issue 2): 17–34. DOI: 10.35808/ersj/2188.

MacDonald, Robert, Hannah King, Emma Murphy, and Wendy Gill (2023). “The COVID-19 pandemic and youth in recent, historical perspective: More pressure, more precarity.” Journal of Youth Studies, 1–18. DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2022.2163884

Miller, Sarah, Merissa Piazza, Ashley Putnam, and Kristen Broady (2023). “Worker Voices: Shifting Perspectives and Expectations on Employment.” Fed Communities.https://fedcommunities.org/research/worker-voices/2023-shifting-perspectives-expectations-employment/

Ong, Justin Guang-Xi (2022). “The Big Read: Understanding why millennials and Gen Zers feel the way they do about work.” CNA TODAY. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/today/big-read/millennials-gen-z-work-younger-companies-big-read-2846841

Teo, Laurel and Han Ei Chew (2023). “Are Singaporeans Ready for the Future of Work?" IPS Exchange, Number 26. ips-exchange-series-26

Edited by Ong Ee Cheng (Social Service Research Centre, NUS)