SSR Snippet - September 2025 Issue 3

Rocking the Boat: How Client Characteristics Shape Therapeutic Alliances for Children with Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Singapore

Diong Zoe Yi & Seah Lay Hoon (NUS)

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, therapeutic alliance, client characteristics, child and adolescent psychotherapy

Introduction

Children who have had adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) face a higher risk of developing mental health disorders later in life. ACEs refer to events such as witnessing or experiencing physical or sexual abuse, violence, parental separation, neglect, or living in a dysfunctional household before the age of 18 (Gomez et al., 2017). Mental health disorders include depressive disorders (Chapman et al., 2004), anxiety, suicidal tendencies (Bruffaerts et al., 2010), and alcohol-use disorders and their comorbidity (Pirkola et al., 2005).

In Singapore, 63.9% of the population reported experiencing at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) in their lifetime. These experiences are strongly related with an increased risk of developing mental health disorders (Subramaniam et al., 2020). Studies in Singapore indicate that having at least one ACE is strongly associated with drug (Gomez et al., 2017) and substance use (Oei et al., 2021). These findings are consistent with the Western psychological literature, which links ACEs to a higher risk of mental health disorders later in life. Thus, to mitigate the deleterious effects of ACEs, it is important for children with ACEs to receive appropriate treatment, such as psychotherapy. Additionally, it is essential to examine factors that increase the efficacy of such treatments — one key factor being the quality of the therapeutic alliance (TA) (Martin, Garske & Davis, 2020; Baier, Kline & Feeny, 2020).

Therapeutic alliance

In the case of child and adolescent psychotherapy, TA is defined as “a contractual, accepting, respectful, and warm relationship between a child/adolescent and a therapist for the mutual exploration of, or agreement on, ways that the child/adolescent may change his or her social, emotional or behavioral functioning for the better, and the mutual exploration of, or agreement on procedures and tasks that can accomplish such changes” (DiGiuseppe et al., 1996, p. 87).

TA has been consistently found to be moderately related to treatment outcomes of mental health conditions regardless of other variables (Martin et al., 2000). Among both adults and youths, a weak TA is associated with higher treatment dropout rates (Shart, Primavera & Diener, 2010; Gergov et al., 2021), whereas a strong TA is consistently associated with positive outcomes regardless of treatment modality (Baier et al., 2020). A poor TA can improve over time, provided the therapist is aware of the rupture and actively works to repair it (Hersoug, Høglend, Havik, von der Lippe & Monsen, 2009).

While many studies show that TA contributes to better treatment outcomes (DiGiuseppe, Linscott & Jilton, 1996; Horvath & Luborsky, 1993; Stubbe, 2018), most of the findings are in the context of adult psychotherapy. In comparison, there is a paucity of research on TA in child psychotherapy, and even less research on factors that enhance TA for children with trauma-related experiences (Zorzella, Muller & Cribbie, 2015). To improve treatment outcomes for children with ACEs, it is critical to conduct more research on how to strengthen TA in this population.

Certain client characteristics unrelated to health can influence functioning and, in turn, help to strengthen TA. These characteristics may include fixed traits such as age, gender, and socioeconomic status, as well as variable factors such as experiences, habits, and personality (Majnemar, 2011).

In general clinical populations, certain client characteristics have been found to correlate with the quality of TA. Positive correlations include clients’ psychological mindedness and motivation for change (Castonguay, Constantino & Holtforth, 2006), while negative correlations include interpersonal difficulties (Gaston et al., 1988; Constantino, Castonguay & Schut, 2002; Paivio & Bahr, 1998). Demographic characteristics such as gender and age have not consistently predicted TA quality; the sole exception is education (Constantino et al., 2002). Therefore, these demographic variables will not be evaluated in this study.

Psychological mindedness

Psychological mindedness is defined as an awareness and psychological understanding of their own and others’ emotions and behaviors (Rai et al., 2015). It reflects a general ability to analyze conflicts and to engage in problem-solving behaviors (Piper et al., 1998), which may contribute to a stronger TA (Piper et al., 1994; Piper et al., 1998). Conversely, low psychological mindedness has been associated with weaker TA (Constantino et al., 2002).

Motivation for change

Another client characteristic that can improve treatment outcomes is motivation, defined as “an intrinsic psychological force that encourages the individual to attempt to master skills that are at least moderately challenging to them” (Majnemer, 2011, p. 1). Clients with higher levels of motivation are more collaborative and more likely to engage in therapy tasks (Bachelor et al., 2007). Treatment motivation is characterized by the client’s determination to engage in treatment, which includes being cooperative and open during sessions, and limiting resistant or rejecting behaviors (Drieschner, Lammers & van der Staak, 2004). These expectations align with the components of TA (e.g., engaging in therapy tasks); thus, a high level of motivation for change is likely to improve TA.

Interpersonal difficulties

In brief psychotherapy, the client’s interpersonal functioning and level of defensiveness are two important determinants of the strength of TA (Gaston et al., 1988). Traits such as hostility, coldness, social anxiety, and non-assertiveness have been found to be negatively correlated with aspects of the alliance in the early stages of therapy (Paivio & Bahr, 1998). Defensiveness is manifested in noncompliance, irritability, and paranoia (Beutler, Moleiro & Talebi, 2002). As defensiveness interferes with learning (Bohart, 2000), defensive clients are less open to feedback and less motivated to work toward change (Gaston et al., 1988). Hence, clients must have the capability to form and sustain trusting relationships; otherwise, they may struggle to relate to others (Gaston et al., 1988) and be unable to build a strong TA.

This exploratory qualitative study examines the variable characteristics of child clients that local practitioners perceive as crucial for strengthening TA and their potential to enhance treatment outcomes.

Research Design

Methodology

We conducted semi-structured interviews of 20–35 minutes with eight professionals. The interviews focused on identifying client characteristics that promote a stronger TA, ultimately improving therapeutic outcomes. In this study, successful therapy outcomes are defined as a reduction in emotional distress or maladaptive behaviors exhibited by child clients at the end of therapy (Weisz, Doss & Hawley, 2005).

Ethical considerations

We obtained the interviewees’ consent to: (i) participate in the interview; (ii) have the interview recorded; and (iii) anonymize any clients and organizations mentioned to ensure no identifiable information is disclosed to the interviewer.

Participants

The eight professionals interviewed included clinical/counseling psychologists, counselors, and social workers, with an average of 5.5 years of experience in their respective roles. All practitioners have worked with children and youths aged 6–18 who have experienced ACEs (e.g., experienced harsh punishments or witnessed marital conflicts). These clients commonly presented with both behavioral issues (e.g., stealing, being dishonest) and emotional difficulties (e.g., anxiety, depression). Older youths tended to exhibit more serious behavioral problems, including involvement in petty crimes like assault or theft.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data using inductive thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke (2006)’s six-phase framework. The data was first transcribed using TurboScribe[1], then coded and organized based on relevance. Constant comparative analysis was applied to identify recurring themes within each interview question.

Results

Most therapists see no difference in client characteristics between general child clients and child clients with ACEs in building TA. General child clients refer to children who have not experienced ACEs but have been diagnosed with other mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety. However, a few practitioners mentioned that children with ACEs experience many unresolved emotions and may have negative perceptions of adults. One practitioner reflected that a strong TA allows the therapist to “rock the boat.” In other words, when a solid relationship is established, the therapist can point out maladaptive behaviors, and the child client is more likely to be receptive to that feedback.

Certain personality traits—such as sociability (i.e., extroversion), confidence, and a desire for social approval—may play a role in improving TA. Sociable children may be more inclined to connect with others, while confident children may have a greater sense of trust in themselves and the world, facilitating rapport-building. Although seeking external validation is not inherently positive, children with this trait may be more agreeable and open to feedback.

One practitioner emphasized that regardless of a child’s personality, the strength of the TA ultimately depends on the practitioner’s ability to build rapport and put the client at ease.

In addition to the child clients’ personality traits, practitioners identified six key abilities in child clients that can contribute to building a stronger TA.

- The child’s ability to persevere. Perseverance is defined as the ability to recover from setbacks and to not give up in the face of difficulties. It involves sustained effort, active engagement, and collaboration during therapy sessions.

- The child’s ability to be receptive, teachable, and open-minded to new perspectives. Generally, children who are receptive are more willing to cooperate with the practitioner.

- The child’s diligence. Diligent children are more likely to exert effort and follow through with therapy tasks and homework. This trait may be reflected in their level of engagement and motivation during therapy sessions.

- The child’s awareness of their inner thoughts and feelings, and their ability to be introspective and reflective. Such traits may facilitate the development of a strong TA as clients who turn inward may be less defensive and more willing to work on their struggles.

- The child’s ability to be emotionally expressive. A child who openly expresses his true feelings may enable the practitioner to better understand his needs. In comparison, the practitioner could find it difficult to grasp the needs of a child who is consistently agreeable yet emotionally withdrawn.

- The child’s cognitive abilities. Children who are cognitively able to comprehend, learn, problem-solve, and reflect may be better equipped to process certain thoughts and experiences, and may be more open to new perspectives.

Discussion

Carl Rogers’ concept of the actualizing tendency emphasizes that all organisms possess an inherent capacity to heal, develop, and fulfil their potential (Csillik, 2013). Thus, the role of child client characteristics in fostering a strong TA is highly significant.

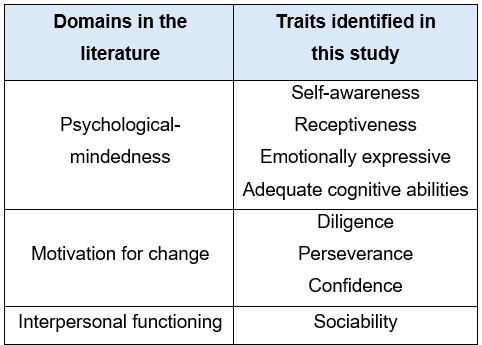

The traits of child clients highlighted by practitioners in this study align with the literature (Table 1). For example, practitioners mentioned the importance of self-awareness, receptiveness, emotional expressiveness and adequate cognitive abilities — traits that fall under psychological mindedness. Meanwhile, confidence, diligence, and perseverance relate to motivation for change, as these characteristics promote adaptability and resilience. Finally, sociability corresponds to the domain of interpersonal functioning.

Table 1: Comparison of domains in the literature and traits identified in this study

Fostering positive traits in child clients

Practitioners suggested a myriad of strategies to foster traits that support a strong TA.

- To enhance motivation for change, practitioners should tailor interventions according to the child’s abilities, readiness, and needs. This approach helps build perseverance by ensuring therapy tasks are appropriately challenging, allowing clients to feel engaged but not overwhelmed.

- Utilizing psychoeducation can help clients better understand their symptoms, behaviors, and the effects of past experiences, thereby enhancing self-awareness and receptiveness to suggestions.

- Demonstrating curiosity and genuineness can foster a sense of safety and security, encouraging clients to be more expressive and socially engaged.

- Focusing on the positives (e.g., the client’s strengths) can help build self-confidence and a sense of mastery.

- Offering validation and empathy helps clients feel understood and supported, encouraging greater emotional expression.

Other considerations to strengthen TA during therapy sessions

Practitioners emphasized the importance of first meeting child clients’ basic need for safety. According to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, fundamental needs such as food, water, and security must be fulfilled before individuals can work toward psychological growth or self-actualization (Freitas & Leonard, 2011). To foster a sense of safety and stability, practitioners recommended assigning child clients a consistent practitioner. Additionally, setting healthy boundaries and modelling appropriate communication — such as showing measured openness — can help clients learn whom they can trust, thereby strengthening the TA. Practitioners also stressed the importance of involving children in goal setting, as it gives them a sense of autonomy and a voice in the process.

Limitations and future research

One limitation of this study is its small sample size, comprising only eight practitioners; future research could benefit from a larger participant pool. Given the significant differences in cognitive development between children and teenagers, it would be valuable for future research to examine these groups separately. Furthermore, as one of the obstacles in building TA with children with ACEs is their lack of trust, future investigations could focus on identifying the mechanisms that facilitate trust-building between therapists and these clients.

Footnotes

[1] Turbo Scribe is an artificial intelligence transcription service that encrypts uploaded data. Only the researcher had access to the data. All data was deleted upon completion of the transcription.

References

Bachelor, A., Laverdière, O., Gamache, D., and Bordeleau, V. (2007). “Clients’ collaboration in therapy: Self-perceptions and relationships with client psychological functioning, interpersonal relations, and motivation.” Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44(2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.44.2.175

Baier, A.L., Kline, A.C., and Feeny, N.C. (2020). “Therapeutic alliance as a mediator of change: A systematic review and evaluation of research.” Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 101921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101921

Bohart, A.C. (2000). “The client is the most important common factor: Clients’ self-healing capacities and psychotherapy.” Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 10(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009444132104

Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006). “Using thematic analysis in psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bruffaerts, R., Demyttenaere, K., Borges, G., Haro, J.M., Chiu, W.T., Hwang, I., ... Nock, M.K. (2010). “Childhood adversities as risk factors for onset and persistence of suicidal behavior.” British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074716

Beutler, L.E., Moleiro, C., and Talebi, H. (2002). “Resistance in psychotherapy: What conclusions are supported by research.” Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1144

Castonguay, L.G., Constantino, M.J., and Holtforth, M.G. (2006). “The working alliance: Where are we and where should we go?” Psychotherapy, 43(3), 271–279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.43.3.271

Chapman, D.P., Whitfield, C.L., Felitti, V.J., Dube, S.R., Edwards, V.J., and Anda, R.F. (2004). “Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood.” Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013

Csillik, A.S. (2013). “Understanding motivational interviewing effectiveness: Contributions from Rogers’ client-centered approach.” The Humanistic Psychologist, 41(4), 350–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873267.2013.779906

Constantino, M.J., Castonguay, L.G., and Schut, A.J. (2002). “The Working Alliance: A flagship for the “scientist-practitioner” model in psychotherapy.” In G.S. Tryon (Ed.), Counselling based on process research: Applying what we know (81–131). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

DiGiuseppe, R., Linscott, J., and Jilton, R. (1996). “Developing the therapeutic alliance in child-adolescent psychotherapy.” Applied and Preventive Psychology, 5(2), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-1849(96)80002-3

Drieschner, K.H., Lammers, S.M., and van der Staak, C.P. (2004). “Treatment motivation: An attempt for clarification of an ambiguous concept.” Clinical Psychology Review, 23(8), 1115–1137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.003

Freitas, F.A. and Leonard, L.J. (2011). “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and student academic success.” Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 6(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2010.07.004

Gaston, L., Marmar, C.R., Thompson, L.W., and Gallagher, D. (1988). “Relation of patient pretreatment characteristics to the therapeutic alliance in diverse psychotherapies.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.4.483

Gergov, V., Marttunen, M., Lindberg, N., Lipsanen, J., and Lahti, J. (2021). “Therapeutic alliance: A comparison study between adolescent patients and their therapists.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111238

Gomez, B., Peh, C.X., Cheok, C., and Song, G. (2017b). “Adverse childhood experiences and illicit drug use in adolescents: Findings from a national addictions treatment population in Singapore.” Journal of Substance Use, 23(1), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2017.1348558

Horvath, A.O. and Luborsky, L. (1993). “The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.61.4.561

Hersoug, A.G., Høglend, P., Havik, O., Von Der Lippe, A., and Monsen, J. (2009). “Therapist characteristics influencing the quality of alliance in long‐term psychotherapy.” Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(2), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.605

Majnemer, A. (2011). “Importance of Motivation to Children’s Participation: A Motivation to Change.” Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 31(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2011.541747

Martin, D.J., Garske, J.P., and Davis, M.K. (2000). “Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.68.3.438

Oei, A., Chu, C.M., Li, D., Ng, N., Yeo, C., and Ruby, K. (2021). “Relationship between adverse childhood experiences and substance use in youth offenders in Singapore.” Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105072

Paivio, S. and Bahr, L. (1998). “Interpersonal problems, working alliance, and outcome in short-term experiential therapy.” Psychotherapy Research, 8(4), 392–407. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptr/8.4.392

Piper, W.E., Joyce, A.S., Rosie, J.S., and Azim, H.F.A. (1994). “Psychological mindedness, work, and outcome in day treatment.” International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 44(3), 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207284.1994.11490755

Piper, W.E., Joyce, A.S., McCallum, M., and Azim, H.F.A. (1998). “Interpretive and supportive forms of psychotherapy and patient personality variables.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(3), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.66.3.558

Pirkola, S., Isometsä, E., Aro, H., Kestilä, L., Hämäläinen, J., Veijola, J., Kiviruusu, O., and Lönnqvist, J. (2005). “Childhood adversities as risk factors for adult mental disorders.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 40(10), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0950-x

Rai, S., Punia, V., Choudhury, S., and Mathew, K.J. (2015). “Psychological mindedness: An overview.” Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 127–132. https://doi:10.15614/ijpp/2015/v6i1/88511

Subramaniam, M., Abdin, E., Seow, E., Vaingankar, J.A., Shafie, S., Shahwan, S., Lim, M.S.M., Fung, D., James, L., Verma, S., and Chong, S.A. (2020). “Prevalence, socio-demographic correlates and associations of adverse childhood experiences with mental illnesses: Results from the Singapore Mental Health Study”. Child Abuse & Neglect, 103, 104447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104447

Sharf, J., Primavera, L.H., and Diener, M.J. (2010). “Dropout and therapeutic alliance: A meta-analysis of adult individual psychotherapy.” Psychotherapy, 47(4), 637–645. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021175

Stubbe, D. (2018). “The therapeutic alliance: The fundamental element of psychotherapy.” Focus, 16(4), 402–403. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20180022

Weisz, J.R., Doss, A.J., and Hawley, K.M. (2005). “Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base.” Annual Review of Psychology, 56(1), 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449

Zorzella, K.P.M., Muller, R.T., and Cribbie, R.A. (2015). “The relationships between therapeutic alliance and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.” Child Abuse & Neglect, 50, 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.08.002

Edited by Ong Ee Cheng (NUS)