SSR Snippet - December 2025 Issue 4

Adult Dynamics and Stepchildren’s Adaptation in Step-family Life in Singapore

Nabilah Mohd (Singapore Children’s Society)

Keywords: Stepfamily, Stepchildren, Role ambiguity, Coparenting, Remarriage

Introduction

Changing patterns of partnership and parenthood have reconfigured families in many countries in recent decades (Sweeney, 2010). Traditional nuclear families — parents and their biological children — have given way to a wider variety of family forms. Propelled by factors such as increased divorce rates and remarriages, step-families have become an increasingly common family type. A step-family typically involves at least one parent who has re-partnered after a previous marriage or relationship and brings a child from that earlier union into the new household (Barnes, 1998).

Mirroring global trends, Singapore too is witnessing shifts in family structures. While figures for step-families are not available in the Singapore census, insights can be inferred from the divorce and remarriage data. The Department of Statistics Singapore (2023) reports that between 2019 and 2023, around half the total number of divorce cases involved families with children. In 2023 alone, these divorces would have affected at least 5,000 children under the age of 18. Concurrently, the data reveals a clear upward trajectory in the number of remarriages in Singapore, rising from 4,862 in 2020 to 6,277 in 2022.

While these figures highlight the growing prevalence of step-families in Singapore, they also raise concerns about the impact of such transitions on children. Dunn (1995) notes that divorce and remarriage are not isolated events but part of a complex chain of transitions that expose children to various potentially stressful changes in the broader social environment.

Yet, despite the potential vulnerability, little is known about how stepchildren experience step-family life in the Singapore context. Most existing research is based on Western contexts, which may not reflect local cultural norms. As Ganong and Coleman (2017) point out, cultural values shape how step-families are experienced and perceived.

This study seeks to explore the lived experiences of step-family members in Singapore, with a particular focus on the impact of parental repartnering on stepchildren.

Methodology

Using a qualitative approach, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 10 step-parents, 10 re-partnered biological parents, and 20 young adult stepchildren, recruited via convenience sampling. Participants (aged 18 and above) came from diverse backgrounds and family types. Young adults were selected for their ability to reflect on childhood experiences. The interviews focused on their lived experiences following the formation of their step-families. Ethics approval was obtained from the NCSS Ethics Review Committee, and all participants received appreciation tokens.

The data were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012). Initial coding focused on identifying descriptive themes such as challenges, adaptive strategies, and advantages related to step-family life. As analysis progressed, a more interpretive theme emerged: adult dynamics — encompassing relationships among the step-couple, biological parents, extended family, and broader social contexts — shaped how stepchildren adjusted to step-family life.

Key Insights

We find that children’s experiences in step-families were shaped not only by structural changes (e.g., gaining a step-parent or step-siblings), but more importantly by the adult dynamics that emerged when a step-family is formed. These dynamics spanned four key domains: (i) the relationship between the re-partnered biological parent and the step-parent (hereafter referred to as the step-couple); (ii) co-parenting between biological parents; (iii) the involvement of extended family; and (iv) the broader social and institutional environments. Together, these adult dynamics can either support or hinder the child’s adjustment to the new family circumstances.

The Step-Couple Relationship: Source of Tension or Foundation of Stability

One of the most immediate and influential shifts is the reconfiguration of the adult relationship in the home when a step-parent is introduced. For stepchildren, this new step-couple partnership became the emotional and structural core of the household and often set the tone for how children made sense of the new family structure and adjusted to its demands.

One of the recurring themes that emerged from parent’s repartnering and step-family formation was role ambiguity, described by Fang and Zartler (2023) as “perceptions of unclarity about relations within families.” Many stepchildren shared that, growing up, the adults in the family did not explicitly discuss or negotiate the step-parent’s role before or even after forming the new family. Without open conversations to clarify expectations or relationships, stepchildren were left to interpret the situation on their own, often leading to confusion. As one stepchild shared:

This experience of role ambiguity echoes Braithwaite and Baxter (2006), who noted that children often lack clear information about how their step-parent came into the family, which can make the transition confusing.

This ambiguity was especially unsettling when it intersected with conflict in parenting styles between the re-partnered parent and the step-parent. When the parental figures were not aligned, stepchildren were caught in inconsistent systems of rules and discipline that can feel unfair or harsh, causing further confusion and even resentment towards the step-parents:

These tensions were further compounded when stepchildren were thrust into an accelerated sense of family, where they were expected to quickly emotionally embrace the new family unit and adopt labels like “Mum” or “Dad” for the step-parent without adequate time to process the transition. While these efforts may have been well-intentioned, many stepchildren often felt emotionally unprepared for such symbolic shifts.

In contrast, when step-couples communicated openly and gave children the time and space to adjust at their own pace, stepchildren described feeling more secure and respected, even if it took time to warm up to the step-parent. Some appreciated being reassured that they were not expected to immediately accept the new partner as a parent but could define the relationship on their own terms. For instance, one stepchild recalled:

Participants also shared how inclusive gestures from the step-couple helped in the stepchildren’s adjustment. One child said:

These experiences highlight that while the step-couple relationship can be a major source of tension for children, it also holds the potential to become a stabilising anchor — when managed with patience, sensitivity, open communication, and a child-inclusive approach.

Co-Parenting across Households: Site of Conflict or Opportunity for Collaboration

In addition to the immediate changes within the step-couple relationship, the ongoing coparenting dynamic between biological parents — who now often resided in separate households — continued to shape family dynamics significantly. For many children, this inter-household relationship influenced their adjustment and emotional security.

A key challenge experienced by many children was the unresolved tensions or negative interactions between their biological parents. The children sometimes become unwilling messengers or felt compelled to take sides. These adult-driven conflicts burdened many stepchildren with feelings of divided loyalty and stress, undermining their ability to adjust smoothly to the transition.

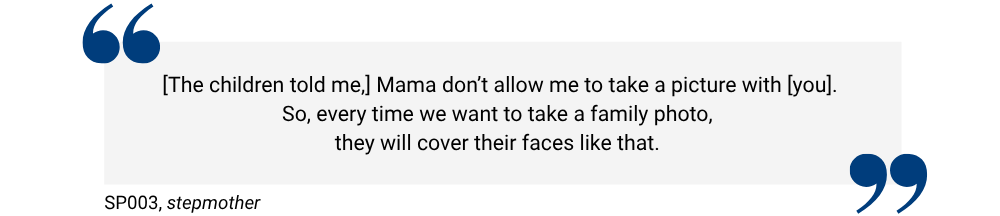

In some cases, the biological parent who is not part of the new household (often the ex-spouse of the re-partnered parent) acted as a gatekeeper, controlling or limiting the step-parent’s involvement with the children. This restrictive gatekeeping manifested in subtle ways, such as discouraging children from acknowledging the step-parent’s role or participating in family activities together. One stepmother shared how her stepchildren were discouraged from openly acknowledging her, recalling:

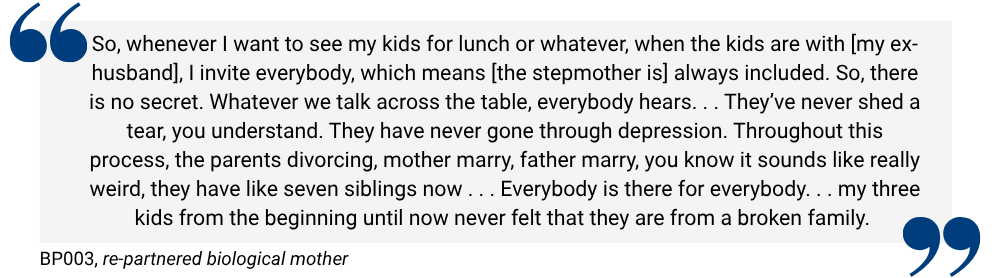

Conversely, when co-parenting relationships between biological parents and step-parents were cooperative and respectful, the children experienced better adjustment. One biological mother described how inclusive co-parenting contributed to her children’s well-being:

Her account illustrates how inclusive and child-centred co-parenting, even across complex family constellations, can help buffer children from the emotional fallout of family transitions. Although such examples of cooperative co-parenting were rare in the dataset, her story underscores the potential for stability and cohesion when adults consciously prioritise openness, mutual respect, and collaboration.

The Role of Extended Family: Reinforcing Belonging or Deepening Fractures

Beyond the immediate household, extended family members, especially grandparents, played a pivotal role in shaping stepchildren’s adjustment process and their sense of belonging in the new family structure.

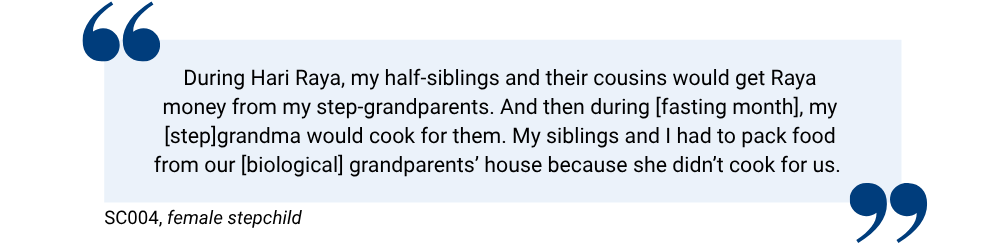

When extended family members failed to acknowledge or include stepchildren, it reinforced feelings of rejection and marginalisation. Such exclusion undermined children’s emotional security and ability to adjust. Several stepchildren recounted moments where they felt “othered” by extended family, especially when kin on the step-parent’s side made subtle — or sometimes overt — distinctions between “biological” and “step” relations. One stepchild, for instance, shared:

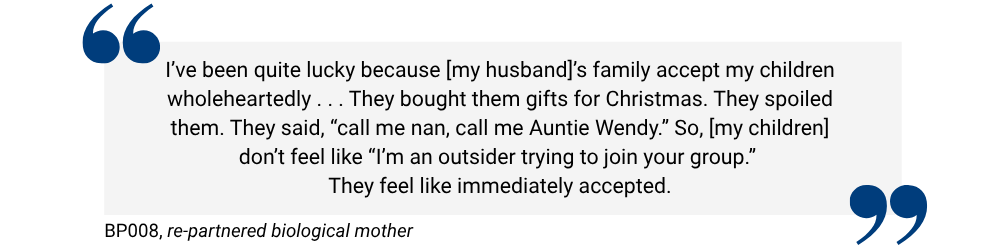

In contrast, when extended kin embraced stepchildren and made conscious efforts to include them, stepchildren were better able to settle into the reconfigured family with a sense of ease and emotional safety. As one re-partnered mother shared:

Institutional and Societal Influences: Reinforcing Stigma or Supporting Adjustment

Aside from the adult dynamics that emerged from within the home, we found that stepchildren’s experiences were shaped not only by relationships within the household, but also by the ways adult actors outside the home — in society and institutions — acknowledge, affirm, or stigmatise step-families. These broader adult dynamics, though more indirect, still significantly affected how stepchildren perceive their family’s legitimacy and their place within it.

A recurring issue was the negative societal stereotypes that cast step-parents as “evil” or “abusive”. These fears were not always rooted in personal experience but were shaped by media portrayals and fairy tales and contributed to early tensions for some stepchildren, undermining trust and delaying emotional closeness within the family.

Schools and formal institutions — as extensions of adult-led systems — also played a role. Several participants shared that their schools did not acknowledge or accommodate step-family configurations. Their family realities were rarely acknowledged in the classroom, where school activities and discussions often assumed a traditional nuclear family model. This lack of representation often left them feeling excluded and invalidated.

Compounding this, several participants also highlighted the lack of adequate resources or targeted support for step-families in Singapore. As one participant described it, “step-families are on their own”. Several wished there had been more preparation or access to resources that could have helped the family adjust.

Despite these challenges, some stepchildren shared experiences where schools played a more supportive role. A few participants recounted encounters with teachers or social workers who took the time to understand their family context. Such moments of recognition, though infrequent, were valued by stepchildren and helped them feel seen and supported:

Discussion

The findings of this study point to a central insight: the adult dynamics that emerge when a step-family is formed play a crucial role in shaping how stepchildren adjust to the new family structure. These dynamics played out across four key relational domains, each capturing a different layer of adult involvement and interaction, from parenting decisions to the wider social messages stepchildren receive. Across these domains, we observed how alignment or tension among adults could either support or hinder stepchildren’s adaptability to step-family life.

A key insight is the pervasive ambiguity around roles within step-families, especially concerning the position and responsibilities of step-parents. This ambiguity often leaves children uncertain and unsupported, illustrating a gap in communication and role negotiation that, if addressed, could significantly ease family tensions and foster clearer expectations.

Moreover, we find that cooperative co-parenting across households, although relatively uncommon in our sample, can improve stepchildren’s experiences. This underscores the potential impact of strengthening inter-adult collaboration beyond the immediate household. Studies have shown that children in step-families fared better when co-parents worked collaboratively (Ganong et al., 2022). Importantly, as other scholars have noted (e.g., Ahrons, 2007; Ganong, Sanner et al., 2021), effective co-parenting does not require the absence of conflict, but rather the minimisation of children’s direct exposure and emotional entanglement in adult disputes.

Crucially, our study highlights that adult dynamics — particularly how conflict is managed and how cooperation is modelled — form the emotional architecture within which stepchildren make sense of their family transitions.

Extended family members also emerged as important influencers, either reinforcing children’s sense of belonging or deepening feelings of exclusion. The variable involvement of extended kin points to the need for inclusive strategies that recognise the broader family network’s role in children’s adjustment.

These findings also point to the role of institutions, such as schools, in mediating step-family experiences. While not always visible in daily family life, these institutions often serve as the only external environment where stepchildren’s needs might be noticed and addressed. While some supportive encounters were noted, many participants reported a lack of support and understanding in schools.

Taken together, these findings call for intentional support systems that equip both adults and institutions such as schools to better navigate and nurture these relationships, ultimately enhancing the support available to stepchildren.

Ideas for Consideration

In light of our findings, we outline two potential areas for consideration.

First, we propose exploring the development of a centralised step-family resource hub. Drawing inspirations from international models like the National Step-family Resource Centre (National Stepfamily Resource Centre, 2024) and Step-families Australia (Step-families Australia, 2021), this hub could serve as a coordinated platform offering tailored support, resources, and capacity-building for step-families and the professionals who work with them. The hub would offer support across these domains:

- Supporting step-couples in building inclusive and stable households.

- Equipping parents for healthy co-parenting across households.

- Engaging extended family in the integration process.

- Training and connecting practitioners and school personnel.

- Providing child-centred communication tools.

This resource hub could be integrated into existing family support frameworks through partnerships with family courts, social service agencies, and schools. For example, it could serve as a mandatory referral point for co-parents during divorce proceedings and for step-couples planning to marry, complementing current co-parenting programs (Ministry of Social and Family Development [MSF], n.d.). Family service centres and schools could also embed the hub’s resources into their ongoing support services, ensuring accessible and coordinated assistance for step-families across multiple touchpoints.

Second we suggest considering efforts to promote step-family-friendly schools. While the centralised resource hub aims to provide comprehensive support, schools represent a uniquely critical environment that warrants focused attention. After the home, schools are often the next major social context where children navigate family transitions. Addressing step-family dynamics within the school setting can help ensure that stepchildren feel supported. Key actions include:

- Training school counsellors and educators to recognise and understand diverse family structures, including step-families.

- Updating school communication practices (e.g., forms, contact persons, parent engagement) to reflect diverse family realities.

- Developing classroom and counselling resources tailored to support children from diverse families, including step-families.

Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. The findings reflect the specific experiences of our participants but, as a qualitative study with a modest sample size, may not be fully representative of the broader step-family population in Singapore.

Furthermore, the study relied on stepchildren’s retrospective accounts of past events, which are subject to the natural limitations of memory and can be influenced by current emotional states or family dynamics.

Finally, the study did not differentiate between various step-family configurations, such as those involving half-siblings, alternating custody, or remarried versus cohabiting parents. Future research should explore how such structural differences affect family dynamics and outcomes.

Conclusion

Children’s adjustment in step-families is shaped by the adult relationships that surround them. When adult dynamics are marked by cooperation, inclusion, and acceptance, children are more likely to thrive. However, unresolved adult tensions — within the home and in society — can complicate their adjustment. Ultimately, creating supportive environments for children in stepfamilies hinges on our willingness and ability to understand and improve the adult world they inhabit.

References

Ahrons, C. R. (2007). “Family Ties After Divorce: Long-Term Implications for Children.” Family Process, 46(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00191.x

Barnes, G. G. (1998). Growing up in stepfamilies. Clarendon Press.

Braithwaite, D. O. & Baxter, L. A. (2006). “‘You’re My Parent but You’re Not’: Dialectical Tensions in Stepchildren’s Perceptions About Communicating with the Nonresidential Parent.” Journal of Applied Communication Research, 34(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909880500420200

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Department of Statistics Singapore. (2023). Marriages and Divorces. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/publications/population/marriages-and-divorces

Dunn, J. (1995). “Stepfamilies and children’s adjustment.” Archives of Disease in Childhood, 73(6), 487–489. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.73.6.487

Fang, C. & Zartler, U. (2023). “Adolescents’ experiences with ambiguity in postdivorce stepfamilies.” Journal of Marriage and Family. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12942

Ganong, L. & Coleman, M. (2017). Stepfamily Relationships. Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7702-1

Ganong, L., Sanner, C., Berkley, S. & Coleman, M. (2021). “Effective coparenting in stepfamilies: Empirical evidence of what works.” Family Relations, 71(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12607

Ministry of Social and Family Development. (n.d.). Mandatory co-parenting programme (CPP). Family Assist. https://familyassist.msf.gov.sg/content/proceeding-with-divorce/divorce-proceedings/mandatory-co-parenting-programme-cpp/cpp-in-english/#

National Stepfamily Resource Centre. (2024). https://www.stepfamilies.info/

Stepfamilies Australia. (2021). https://stepfamily.org.au/

Sweeney, M. M. (2010). “Remarriage and Stepfamilies: Strategic Sites for Family Scholarship in the 21st Century.” Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 667–684. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00724.x

Edited by Ong Ee Cheng (National University of Singapore)