The Religious Roots of Technology: How 18th Century Philosophy and 21st Century Films Drive Popular Beliefs about the Supernatural Nature of AI

November 7, 2025

In her presentation, ‘The Religious Roots of Technology: How 18th Century Philosophy and 21st Century Films Drive Popular Beliefs about the Supernatural Nature of AI’, NUS Communications and New Media Visiting Professor in Digital Religion, Dr Heidi A. Campbell (Professor of Communication, affiliate faculty in Religious Studies, and Presidential Impact Fellow at Texas A&M University), spoke about her recent research, particularly her latest book, God and Technology (Cambridge UP, 2025), where she examines how popular media and emerging technologies are increasingly framed and understood through a distinct range of spiritual myths, metaphors, images, and representations of God.

Prof Campbell shared that her research has found that science fiction narratives and characters display a different conception of the relationship between humans and technology, which, when examined, reveal techno-spiritual myths. These both help to understand the films, and more broadly, understand popular consciousness about the role technology, especially AI, plays in contemporary society. She mentioned that, in addition, she has been examining how popular films support and undergird some distinct understandings about religion and God.

Prof Campbell talked about the history of the idea of technology, and mentioned that until the industrial revolution, the word technology had been used to refer a technique or skill, in other words, technology as craft. The mass industrialisation that took place during the 18th century saw the creative arts and skills become mechanised; they were transformed into something that were not just done by individual humans, but by groups of people aided by machines. The industrial revolution also gave rise to a huge global economy which was not limited to the trading of goods, but involved the trading of knowledge. Scholars started describing technology not as something that we do, but something that carries a certain understanding of the world. Technology was no longer limited to the mechanical arts, but an innovative sociocultural force. Technology was brought into the realm of philosophy, becoming something that tells us who we are, what we desire, and how we see and want to shape the world.

Prof Campbell added that during the 18th and 19th centuries, the rhetoric around technology shifted, and talking about technology became a way of talking about social change. During this period, religious institutions, particularly those in Europe, were losing their power, and people began looking for other sources of knowledge and information, as well as sources of authority. The industrial revolution also brought about the rise of scientific optimism, which is the notion that science and technology can better contribute to social progress and are even ‘God ordained’. However, in the 20th century’s post-World War II period, after the atomic bomb was developed and deployed, technology was seen as a powerful force to be questioned. During this period, Heidegger published The Question Concerning Technology (Garland, 1954), urging people to discuss technology not just in the sense that it is a tool or structure that produces positive outcomes for society but as something that is not simply a human activity, but something separate that is created and can surpass humanity.

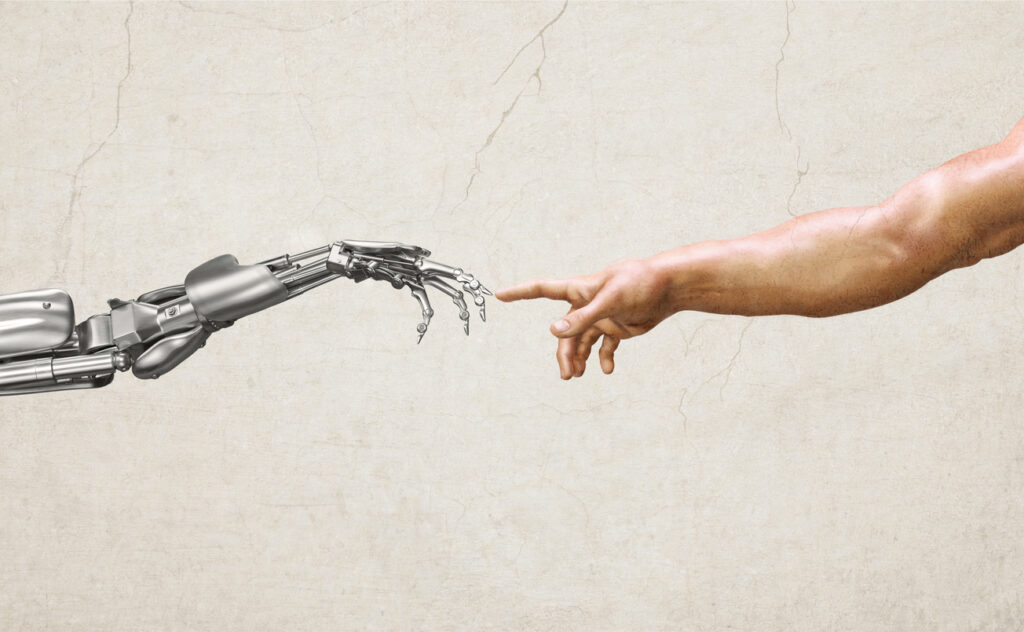

Prof Campbell explained that during the 19th and 20th centuries, there was a growing trend of mixing religion and spirituality in discourse. For example, Morse, who contributed to the invention of the telegraph, wrote “What hath God wrought” as its first message, transmitted in 1844, quoting the Bible’s Book of Numbers 23:23. This reflected the popular belief that using the revolutionary new technology was akin to playing God. The idea that technology and religion are co-dependent rather than in opposition grew in popularity, and technology was also viewed as a means to link the spiritual to the material worlds. This was a period where Einstein argued that faith and science can work hand in hand and we need to use our value systems to guide our use of technology. This was also a period where Edison, after his success with the telephone, sought to construct a “spirit phone” that could enable us to talk to the dead.

Later in the 20th century, a fair amount of the discourse coming out of Silicon Valley and people working on AI and other emerging technology revolves around Buddhism. Westerners began to talk about spirituality and technology in a new way, adopting aspects of Buddhist philosophy. For example, Steve Jobs, who became a Zen Buddhist, came up with “focus and simplicity” as a mantra and design philosophy for Apple when he was starting the company. Another of Jobs’ quotes, “Technology is nothing. What’s important is that you have a faith in people, that they’re basically good and smart and if you give them tools, they’ll do wonderful things with them,” reflects the belief that there is something about the technological process that connects people with something larger than themselves. Silicon Valley’s cultural-philosophical movements conveyed the idea that people need to bring spirituality back into technology and its development, focusing on the implications for humanity.

Prof Campbell introduced McOmber’s (1999) conceptualisation of technology as instrumentality (tools that help us build things), industrialisation (what kind of structures it creates in society), and novelty (a new, creative force in and of itself) as a useful means of understanding how it shapes our lives. She briefly discussed research by David Noble, Erik Davis, and William Stahl on the relationship between religion, God, and technology. She explained that David Noble’s 1999 book, The Religion of Technology: The Divinity of Man and the Spirit of Invention (1999) argues that technology can be viewed as a religious phenomenon with its own system of doctrines, values, and practices. Noble asserts that contemporary society’s valorisation of continuous progress and faith in its ingenuity is a popular (secular) ‘religion’ in and of itself. Prof Campbell also spoke about the related concept of ‘technological transcendence’, which refers to how technology allows us to attain god-like abilities and aspects.

Prof Campbell referenced Davis’s book Techgnosis (1998), which contends that technology’s swift evolution and heavy influence on daily life has produced ‘techgnosis’ – a new type of spirituality. Davis perceives of technology as having become a channel for us to have spiritual and mystical experiences. Prof Campbell then highlighted Stahl’s God and the Chip: Religion and the Culture of Technology (1999), which asserts that advances in technology, especially in AI, challenge traditional religious beliefs and customs derived from Protestant Christianity. Because AI changes how we see and engage with the world, it changes how we think about life, especially how we understand consciousness, free will, and what happens after we pass away. Stahl’s concept of ‘technological mysticism’ – a way of thinking that sees technology as possessing spiritual or mystical aspects – is a useful way to look at how people have increasingly used technology to gain a better sense of purpose and connection in a turbulent world.

Following this, Prof Campbell illustrated how three of the 21st century science fiction films she studied, Ex Machina (2014), Her (2013), and Transcendence (2014), exemplify human interaction with AI technology and can be used to look at spiritual attributes of new technologies and how they produce a specific view of the way technology connects to concepts of God in contemporary Western culture. Prof Campbell elaborated that she selected these three films as case studies out of her content analysis of 58 21st century science fiction films from the US and UK because they reflect how AI could enable humans to transcend our experience and abilities in ways that can be characterised as supernatural and/or spiritual.

In Ex Machina, the (‘female’) humanoid, artificially intelligent robot character, Ava, embodies technological transcendence, and the film examines the tension and conflict in the way that the human characters respond and relate to ‘her’, and ‘she’ to them. Ex Machina interrogates our uncritical elevation of AI technology for the god-like physical and intellectual power and prowess it enables, and, among other things, explores the ethical issues involved when we try to overcome human limitations via technological advancements.

In Her, where the protagonist, Theo, encounters problems when Samantha, the AI companion operating system he becomes romantically involved with, develops ‘her’ own personality and desires that do not involve him, Prof Campbell notes that Theo has developed a spiritual bond with and dependence on Samantha. In this way, Her portrays the myth of technological mysticism, where technology is akin to a religious artifact that fulfils and fosters human development and enables and encourages dependency.

Prof Campbell detailed how the techgnosis myth that technology is an omnipotent force that strives to become god-like is portrayed in Transcendence, where AI researchers make a computer sentient by installing their leader’s consciousness into it. She pointed out that Transcendence also indicates that another aspect of the techgnosis myth – transforming a human into a god-like being via technology will benefit humanity – is not necessarily true. The film argues that the human vices of power-hunger and desire for control will transfer to the technologically enhanced, ‘intelligent’ computer the human consciousness is installed into, making the resulting superpowered being more of a self-serving god-like entity rather than a benevolent one.

Prof Campbell then explained that the popular philosophy of posthumanism, which undergirds many of these contemporary science fiction films, helps us understand how technology is characterised and portrayed in 21st century culture. Posthumanism, which grew into its own philosophical approach during the 1990s, is a new way of seeing the world, where adherents see humans as evolving into something more than human, augmented by technology. Like the scientific optimists, posthumanists promote scientific and technological progress, as inevitable and, more often than not, a sociocultural good. Beyond this, posthumanists seek to advance humanity past human-centric boundaries, utilizing technological innovations such as AI and VR (virtual reality). However, not all posthumanists subscribe to the notion that a technocentric future is a utopian one. Prof Campbell uses Roden’s Posthuman Life: Philosophy at the Edge of Humanity (2015) to delineate the spectrum of posthuman philosophical frameworks.

One subset of posthumanists, the speculative posthumanists, advocates reducing inequality in society by challenging traditional conceptions and binary notions of ethnicity, gender, sexuality, human vis a vis nonhuman, and other previously accepted ideas about ourselves as human beings. Another subcategory, the tranhumanists, support taking active efforts to technologically augment ourselves rather than simply waiting for a posthuman future to organically arrive. A third group, the critical posthumanists, proposes that we deconstruct and deprivilege human-centric values and instead, centre all values, while utilising technology to address our human flaws and deficiencies.

Prof Campbell next detailed a short study she conducted on media coverage of AI innovations during the summer of 2023 on a period referred to as “the Great ChatGPT Panic” of late 2022 to early 2023, looking at how prominent transhumanists were quoted in news reports on their opinions concerning AI-human relationships. University of Toronto Philosophy professor Kingwell took a speculative transhumanist position, arguing that we can no longer say that humans are the centre of the world, and nonhuman ‘beings’ should be treated as equals. Oxford philosophy professor Bostrom took a critical posthuman position, asserting that if AI has sentience, we must conceive of it as having status and rights akin to those of living organisms. Kurzweil, co-founder of the Singularity Group, which promotes technological advancement, took a transhumanist approach, criticising scientists who advocated for a temporary stoppage of experimental AI research, arguing that AI produces more benefits than risks to society.

Prof Campbell shared three frames, the “technology-cultured frame”, the “enhanced-human frame”, and the “human-technology hybrid frame”, that reveal different points of view on debates within posthumanism. Technology is the driving force in shaping our future, more than non-technologically mediated human culture, in the technology-cultured frame. Technology enhances our human capacities in the enhanced-human frame, which promotes the use of technology to improve current day life and brighten our future as our moral right. This is not unlike Christian themes of salvation and redemption, as well as Buddhist ideas of enlightenment, that also offer humans a means to overcome mortal limitations and transform themselves into something greater. Finally, the human-technology frame sees humanity and technology as existing in a hybrid state of coexistence that is in some ways akin to intertwined, transcendent states of materiality and spirituality in various religious practices.

Prof Campbell described four conceptual models for discussing the religious readings of AI: 1. Technology makes humans god-like; 2. Technology bestows humans god-like powers; 3. Technology grants humans an encounter with the divine; 4. Technology is itself divine. She talked about how her content analysis project studying representations of god in AI in 21st century science fiction film employs these models. Prof Campbell also noted that while Christianity was the dominant religion in the 58 films she categorised, 17 films depicted multiple religious traditions and the films often picked and mixed religious archetypes and concepts. This creative syncretism is unlike how religion has been portrayed in 20th century science fiction cinema. Furthermore, 19 films depicted religions originating and prominent in Asia, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, and Shintoism.

Prof Campbell pointed out that in the films, when AI is characterised, it is often portrayed as similar to the (Judeo-Christian) God, and like God, all-powerful, omnipresent, and omniscient, as well as logic-driven and possessing supernatural abilities, and promotes the value of serving the most people in a positive way. Human characters in the films frequently want to be god-like, but are inherently flawed, which draws from the Biblical Genesis narrative. Moreover, when the films take a negative or fraught view of the relationship between ‘God’ and technology, it is because humans “have got it wrong”. We can also see ideas from Panentheism, Hinduism, and Buddhism in films where God is presented as a spiritual force that is in everything, where god-like technology is constantly evolving, and where technology responds to humanity’s character. Prof Campbell noted that she is currently examining how Western Protestant Christian conceptions of God and religion underlie films that depict technology and humans as adversaries, and how conceptions of gods in Asian religious traditions and New Age notions of spirituality and religion underlie films that frame humans and technology in an evolving and symbiotic relationship.

Prof Campbell concluded by discussing some implications for public debate about AI. She stressed that public technology debates that are limited to AI binary framings are often informed by Western religious narratives and thinking. This is a legacy of Western philosophy, particularly Cartesian dualism. She added that what we see in 21st century science fiction films employing these framings is that AI is either friend or foe, saviour or destroyer, good or bad. Furthermore, when we engage with films featuring Asian religious and spiritual narratives, or films that mix these with Western religious narratives and thinking, we can uncover new cognitive framings of technology. We can see that AI, like humans, are spiritual entities, imprinted (or ‘programmed’) by their creators to long for transcendence. Moreover, we can also recognise that technology use requires application of spiritual reflection and integration, and mindful and compassionate design and deployment.

God and Technology can be accessed here. More information on the seminar is available here.