Unlocking Singapore’s Multilingual Heritage: AI Brings Jawi Newspapers into the Digital Age

December 1, 2025

Where Expert Thought Leads the Conversation

BY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR MIGUEL ESCOBAR VARELA

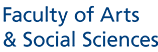

On 13 February 1942, Singapore was on the brink of collapse. World War II had come to Southeast Asia, and the city would fall to Japanese forces in just two days. That morning, the Utusan Melayu, one of the region’s prominent newspapers, faced its own crisis. The paper could only manage to print a handful of copies of its daily edition. In a desperate act, senior managers themselves took to the streets, hawking newspapers like common vendors. Among them was Yusof Ishak, a co-founder of the paper who would go on to become Singapore’s first president. This episode, later recounted by Yusof Ishak himself, is indicative of his tenacity and his unwavering desire to establish a vibrant Malay-language newspaper chronicling the world at a pivotal time for Singapore.[i]

Malay, the national language of Singapore (and one of its four official languages) was the island’s lingua franca for centuries. Thousands of Malay-language newspaper pages, from the 1870s onward, lie in the archives of the National Library of Singapore. These newspapers hold invaluable stories of Singaporeans’ shared past, but they remain largely inaccessible to modern readers and researchers. The main obstacle is the script: until the 1970s, these papers were written in Jawi, a modified version of the Arabic script used to write Malay. Today, few can read it. But the problem goes deeper than literacy. Jawi doesn’t fit into modern information systems, which means researchers can't easily access these archives, search through them, or even display them properly.

Now an ambitious project is underway to change that. My team and I are using artificial intelligence to transcribe, transliterate, and render these historical newspapers fully searchable. The goal is simple but profound: to ensure that all Singaporeans can access these voices from the past, and that historians and researchers can analyze how issues, ideas, and communities evolved through decades of Malay-language journalism.

The technical challenge, however, is formidable. Jawi is not simply Arabic script transplanted to the Malay language; it contains modified letters and orthographic conventions specific to Malay. Sometimes, vowels are not written down, and the meaning of a word depends on context. The word “بنتڠ” could mean both “bintang” (star) or “benteng” (fortress). This is the type of task where AI systems are potentially useful, as they can consider an entire sentence or passage and decode the context. However, commercial AI systems consistently fail to recognise Jawi, perhaps because it is not a significant portion of the data they are trained on. When tested, mainstream AI chatbots don’t just struggle with Jawi—they hallucinate, confidently generating plausible-looking but entirely incorrect transcriptions that could mislead researchers and corrupt our historical record. Take, for example, the word “جوك ” or “jugak”, an old variant of the word “juga”, which means “also”. ChatGPT consistently misinterprets it as “joget”, which means dance, injecting the texts with improbable, and sometimes hilarious, dance allusions. Anthropic’s Claude AI seems to think this word means “hukum” or “law”, and it tends to infuse texts with odd legal interpretations.

This is where homegrown innovation makes the difference. Rather than relying on off-the-shelf solutions, our research group is developing our own tools. We are starting with SEA-LION (Southeast Asian Languages in One Network), a family of models developed by AI Singapore that were specifically designed to work with regional languages, including Malay. In contrast to the commercial platforms, the models developed by AI Singapore are “open-weights”. This means that researchers like us can download these models and change the “weights” — that is, the numbers that make these models work. Through a process called “supervised finetuning”, we recalibrate these weights to suit a specific task. For this process to work, we create a relatively small but very accurate set of examples, which we then use to train and validate our resulting model. To create this dataset the Jawi experts in our team manually annotate thousands of examples, both transcribing the Jawi directly and transliterating into Rumi, the Romanized version of Malay common today. To ensure high fidelity, every data point is independently evaluated by at least two experts.

Another key difference between our tools and commercially available platforms is that we want our models to tell us when they are likely to be wrong. For this, we use a range of techniques from a field called Explainable AI (xAI) to produce confidence scores and identify cases where the accuracy is in question. When this happens, we can direct our human experts to particularly difficult passages, which might, for example, contain unusual words or names.

The potential impact of this project extends beyond preservation. Just as recent digital analyses of the archives of The Straits Times has yielded fresh insights into Singapore’s English-language press history, making Jawi newspapers searchable will enable similar longitudinal studies of Malay-language journalism.[ii] Researchers will be able to track how communities discussed independence, trace the evolution of social concerns, and understand how people of different eras grappled with the challenges of their times. It recognises that Singapore’s story cannot be told in one language alone, and that technological progress means little if it leaves entire communities’ histories behind. By making these newspapers accessible, we empower all Singaporeans, regardless of their linguistic backgrounds, to understand the complex, multilingual society they have inherited and continue to build together.

Our work is funded by the Societal Impact Scheme of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the National University of Singapore (NUS) and our team includes historians, computer scientists, and experts in Jawi.

Faizah Zakaria and Seng Guo-Quan are leading historians of our region, and Min-Yen Kan is a world-renowned expert in Natural Language Processing and AI. I sit somewhere in between these disciplines. I am fluent in Malay, and my work involves writing software for the preservation and analysis of cultural heritage, but in terms of formal training, I am neither a historian nor a computer scientist. I like to think of myself as a translator of sorts, someone who brings people from different disciplines to work together. This is also what I do in my role as deputy director of the NUS Centre for Computational Social Science and Humanities (CSSH). This joint initiative from the NUS School of Computing and the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences aims to boost connections across disciplines, serve as a catalyst for interdisciplinary research that helps us better understand Singapore, and tackle complex problems that a single discipline is unable to solve. For example, one of the projects that the Centre has funded through a seed grant looks at how Social Service workers can use AI chatbots as part of their work. This project is led by Yi-Chieh Lee (NUS School of Computing), Jungup Lee (NUS Department of Social Work), Gerard Chung (NUS Department of Social Work), and Renwen Zhang (NTU Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information). Their goal is not to supplant social service workers, but to empower them to use culturally sensitive, error-aware systems like the ones I described before, helping them better provide vital support to those in need. In my mind, the work of my colleagues exemplifies AI at its best: culturally specific, historically informed, and deployed in service of the public good rather than mere commercial efficiency. These are the goals that my own research team also strives for, and the type of research that the CSSH aims to support.

This brings us back to the Utusan Melayu, the newspaper from the beginning of this essay. In its first issue, published on 29 May 1939, here’s how the founders stated the newspaper’s purpose: “to exchange ideas for the common good.”[iii] When we use AI to study and understand these newspapers, we honour that purpose. With technology, we are making knowledge accessible for the common good.

NOTES

[i] Nik Ahmad Bin Haji Nik Hassan. “The Malay Press.” Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 36, no. 1 (201) (1963): 37-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41505523

[ii] “From 1845 to 2020: Singapore & the world through The Straits Times headlines.” (30 October 2020). The Straits Times. Retrieved October 31, 2025, from https://www.straitstimes.com/multimedia/graphics/2020/10/175-years-headlines/index.html

[iii] Nik Ahmad, op. cit.

Associate Professor Miguel Escobar Varela is Deputy Director of the NUS Centre for Computational Social Science and Humanities, and teaches at NUS English, Linguistics and Theatre Studies (NUS Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences). In his research, he uses computational methods to study the cultural heritage of communities that speak Malay, Indonesian, and Javanese.