Four Frames, One Punch: The Surprising Power of the Comic Strip

November 27, 2025

Where Expert Thought Leads the Conversation

BY ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DEBORAH SHAMOON

The humble comic strip is an instantly recognisable, ubiquitous narrative format. Developed in American and European newspapers around the turn of the twentieth century, the four-panel format is now everywhere. How does it work? Why does it persist?

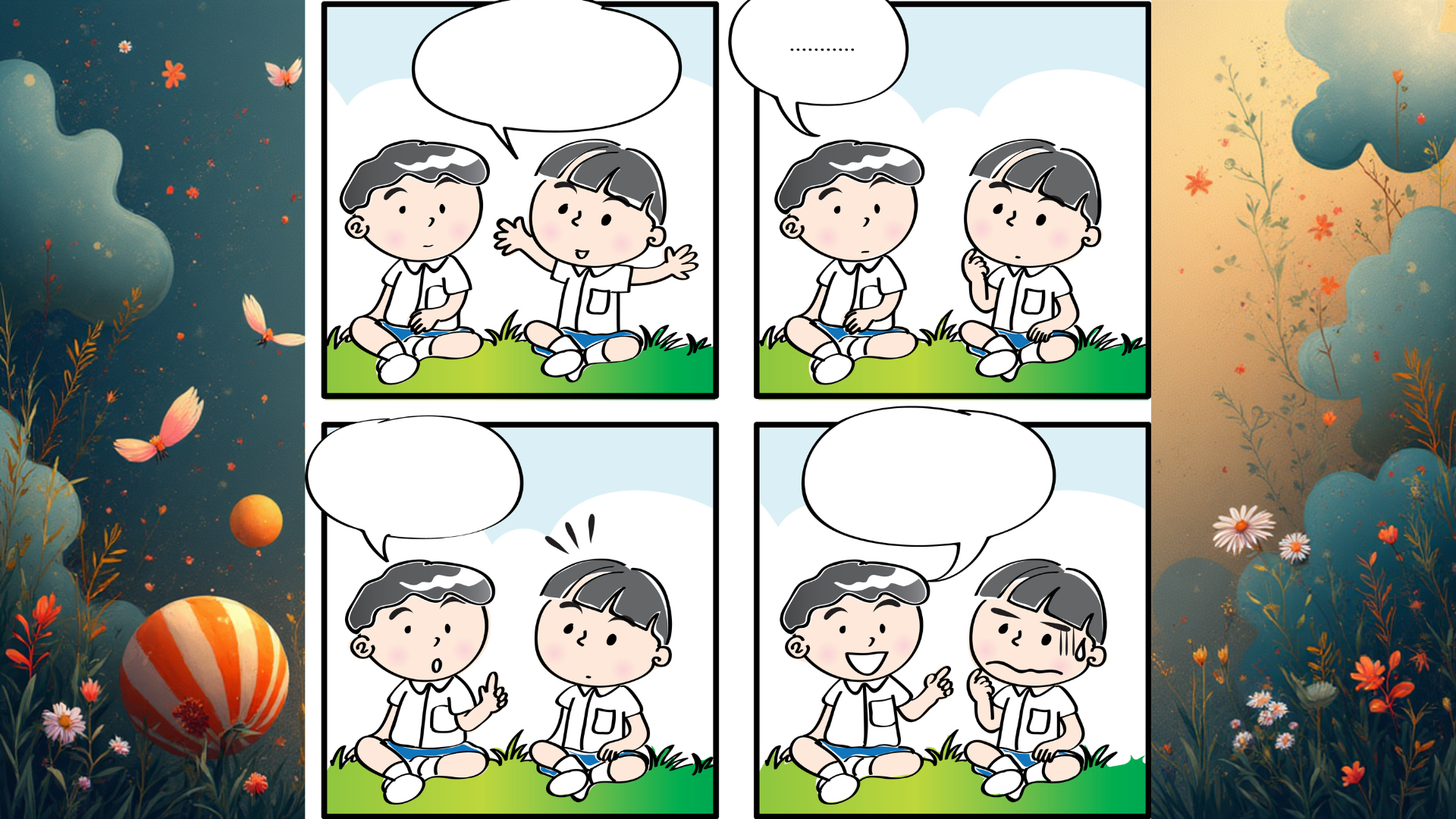

American cartoonist Bill Griffiths breaks down the four-panel comic to its most basic format in this strip, originally published in his series Zippy the Pinhead on 20 December 2008. He defines the narrative function of each of the four panels as, “Intro. Set Up. Conflict. Punchline!”

While comic strips are usually conflated with gags ending in a punchline, that is not their only function. From their inception to the present day, across cultures, four-panel comic strips present a variety of genres, from melodrama and adventure to autobiography, even in informational contexts and public health messaging. There has been extensive scholarship on the history of newspaper cartoons, and examination of the visual features of individual strips. Yet despite its ubiquity, scholars have paid surprisingly little sustained attention to the narrative form of the four-panel strip itself. The four-panel grid constitutes a distinct visual grammar, a set of repeatable, cross-culturally legible strategies that orchestrate timing, emphasis, and audience inference.

In Japan, the structure of the four-panel comic strip is often described using the poetic term kishōtenketsu, but this is misleading. Kishōtenketsu 起承転結 is a four-line poem or four-part structure in poetry or prose that developed in China around the tenth century and was imported to Japan. Cartoonist Okamoto Ippei used the term kishōtenketsu to describe four-panel comic strips in an article for the magazine Asahi Graph in 1927.

However, Okamoto’s use of this elevated poetic term was part of his larger project of creating high culture cachet for his emerging art form, or rather, for making the case that cartooning is art (bijutsu) and not merely lowbrow entertainment. Okamoto was also one of the first and most enduring voices to propagate the myth that manga developed from classical Japanese art. In fact, manga developed in the early twentieth century in response to the translation of popular four-panel newspaper strips such as Bringing Up Father.

The concept of kishōtenketsu, or literally, introduction, development, turning point, conclusion, is similar to the four-part structure Griffiths calls intro, set-up, conflict, punchline. But as this form already appeared in the US and Europe before being imported to Japan, it is a case of parallel development, not direct influence. The fact that this four-part structure is so easily understood worldwide also indicates that it is not unique to any particular cultural tradition.

Regardless of where this format comes from, it is an incredibly powerful communicative tool, because it is so simple and well-recognised. The format of the four-panel comic strip does not always feature a conclusion or a punchline in the final panel. Neither is the number always four; it can vary between three and five panels with the same internal narrative structure.

The fairy tale offers a more useful parallel to the narrative structure of the comic strip than classical poetry. Like a fairy tale, the comic strip has a fixed, predictable format that readers anticipate from beginning to end. We know that when a story begins “once upon a time,” it will end with “happily ever after.” Other cultures have similar fixed phrases, such as in Japanese “mukashi mukashi” (long, long ago) and “medetashi medetashi” (all’s well that ends well). Even when a fairy tale subverts the expected ending, it still relies on audience expectations. Tzevetan Todorov calls the ending of the fairy tale “transformed equilibrium.”

The fourth panel of a comic strip also functions in this way. The first one or two panels sets up a narrative, a conflict arises in the middle panel, and the fourth panel provides transformed equilibrium, calling back to the set-up. This may be in the form of a gag, but not always.

This expectation of the dramatic tension caused by transformed equilibrium in the final panel drives the narrative of strips in every genre. Due to the inherent structure of this very rigid form, it gives shape to content that would otherwise lack form. This makes it ideal for autobiography, slice-of-life, and informational genres.

Lynda Barry is one of the greatest artists whose strips transcend the gag format. Ernie Pook’s Comeek, which ran in US alt-weekly newspapers from 1979 to 2008, chronicles the lives of a group of children and young teens in 1960s Seattle. Loosely based on Barry’s own experiences, the strips range from funny to heartbreaking, portraying the world of children with startling immediacy. While some narrative arcs emerge over time, most strips are brief vignettes, given shape by the four-panel format.

The four-panel format also features in the Japanese slice-of-life (nichijōkei) genre, also called kūkikei, meaning “atmosphere” or “vibes.” In English-speaking fandom, this genre is sometimes called Cute Girls Doing Cute Things (CGDCT). As the various names imply, there is typically no plot, just vibes. There is usually no single main character, but a group of cute girls. For example, Lucky☆Star, by Yoshimizu Kagami, is about a group of high school girls who are fans of manga and anime. The deep-cut references to manga and anime fandom attract readers who are also fans, while the four-panel format gives structure, compensating for the lack of plot. Similar series in the four-panel format include Azumanga Daioh by Azuma Kiyohiko and K-On by Kakifly.

Comic strips were originally designed to sell newspapers in the early twentieth century, but now they have moved online. Even with the unlimited space afforded digital comics, unlike print newspapers, the four-panel form endures because it is so useful. Even memes use the four-panel format.

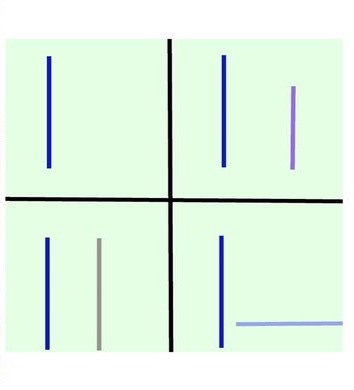

One of the most widely circulated and enduring memes is loss.jpg (ref. image on the right), which was originally based on a four-panel digital comic by Tim Buckley called Ctrl+Alt+Del. In 2008, Buckley published a wordless strip titled “Loss,” depicting the main character’s girlfriend suffering a miscarriage. As the previous strips up to this point had featured crude jokes about video games, readers found this tonal whiplash insincere, cringe-worthy and eminently mockable. Parodies of the strip quickly proliferated, replacing the characters in the original strip but leaving them in the same relative positions. Soon this parody evolved into minimalist loss memes, in which inanimate objects, shapes, or even just lines represented the figures in each of the four panels.

One of the most widely circulated and enduring memes is loss.jpg (ref. image on the right), which was originally based on a four-panel digital comic by Tim Buckley called Ctrl+Alt+Del. In 2008, Buckley published a wordless strip titled “Loss,” depicting the main character’s girlfriend suffering a miscarriage. As the previous strips up to this point had featured crude jokes about video games, readers found this tonal whiplash insincere, cringe-worthy and eminently mockable. Parodies of the strip quickly proliferated, replacing the characters in the original strip but leaving them in the same relative positions. Soon this parody evolved into minimalist loss memes, in which inanimate objects, shapes, or even just lines represented the figures in each of the four panels.

Any series of four images arranged in this format may be considered a loss.jpg meme. Despite its inherent silliness, the fact that the loss meme is still circulating after more than a decade shows the power of the four-panel format. Even with the most minimal content, we still recognize the pattern and use it to make meaning.

The transformed equilibrium of the final panel creates a structure that artists can play with endlessly. Few other narrative forms have this fixed quality. This is why the comic strip works equally well for gags, slice-of-life, or for non-fiction public messaging. Despite the many changes in print and digital media, the comic strip seems likely to continue into the future, as a particularly robust form of communication.

Associate Professor Deborah Shamoon’s areas of expertise are Japanese literature, film and popular culture, with especial focus on manga (comics) and animation;, and her research focuses on representations of girls and young women in Japanese media (including film, animé, manga, novels and magazines) from the 1920s to the present. This piece is based on a chapter of her forthcoming book, Text and Image: Making Meaning in Manga and Comics (University of Minnesota Press, 2026).