SURESHKUMAR MUTHUKUMARAN

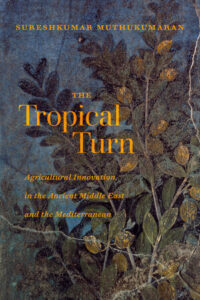

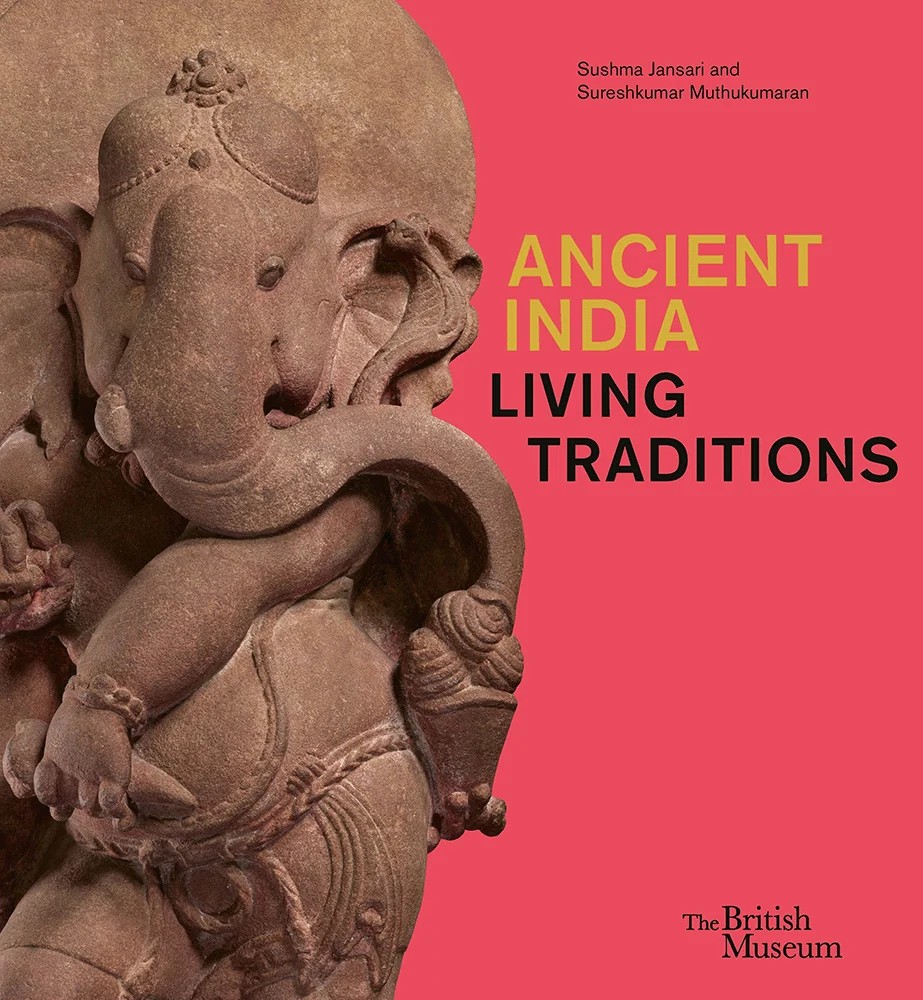

Sureshkumar Muthukumaran is Assistant Professor at the NUS Department of History. He investigates interactions between peoples in ancient Afro-Eurasia with an eye to examining long-distance connectivity and uses the anthropogenic mobility of cultivated plants and other biological materials (such as fauna, diseases, etc.) as a roadmap to understand cross-cultural exchanges and the movements of people through space and time. Dr Muthukumaran has published five articles, five book chapters, and two books, most recently Ancient India: Living Traditions (British Museum Press, 2025), co-authored with S. Jansari in conjunction with an exhibition. His 2023 book The Tropical Turn: Agricultural Innovation in the Ancient Middle East and the Mediterranean (University of California Press) has received two prestigious awards: the 2024 Jerry Bentley Prize in World History from the American Historical Association (AHA) and the 2025 Mary W. Klinger Book Award from the Society for Ethnobotany. The book has also been featured in the New Books Network podcast and the Chinese translation will be published by Jiuzhou Press, Beijing. The Tropical Turn chronicles the earliest histories of familiar tropical and subtropical Asian crops in the ancient Middle East and Mediterranean, from rice and cotton to citruses and cucumbers. Drawing on archaeological materials and textual sources in over seven ancient languages, it unravels the breathtaking anthropogenic journeys of these familiar crops from their homelands in tropical Asia to the Middle East and Mediterranean, showing the significant impact South Asia had on the ecologies, dietary habits, and cultural identities of peoples across the ancient world.

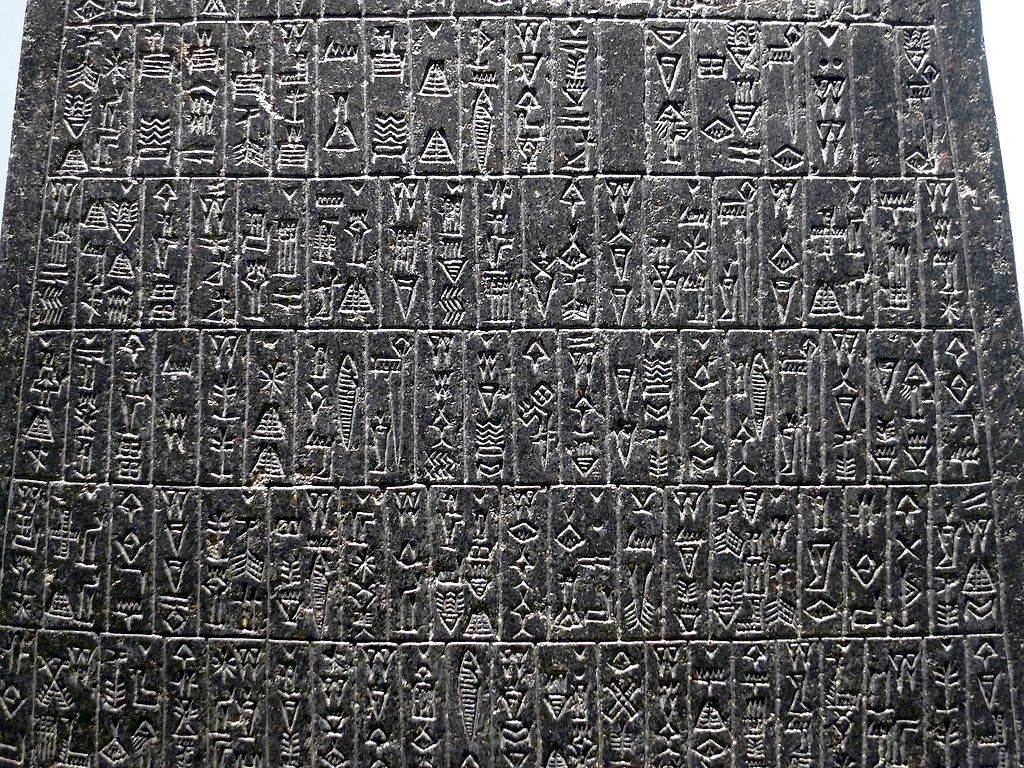

1. How did you initially become interested in exploring cross-cultural exchanges in ancient civilisations?  If you’d met me as a child, I’d probably have told you I was going to become a palaeontologist. In some ways, my interest in distant and deep pasts of both humans and non-humans alike has been an enduring one. My initial training as a historian in a British university context was very broad, covering everything from the ancient Middle East to the colonial Americas. Ancient history had a particular draw as it employed a very diverse range of sources including inscriptions, administrative archives, specialist treatises, archaeological finds and art historical materials to uncover the past. My interest in cross-cultural exchanges was also fuelled by my learning of a number of ancient languages like Akkadian, Sanskrit, Greek, and Latin. The world-class teachers and researchers I came into contact with played no small part in my decision to specialise in ancient history. 2. What challenges did you encounter when conducting research for The Tropical Turn? Mastering a number of ancient languages to a degree of competency was the greatest challenge as the book drew on multiple sources in different ancient languages. Typically the practice of ancient history is very fractured and specialists of different languages or language families work in silos. Greek and Latin specialists would fall in Classics, Sumerian and Akkadian ones in Assyriology, and Sanskrit and Tamil ones in Indology and so on. A number of scholars have attempted to bridge these modern scholarly divisions but there still remains a great deal of work to be done in deconstructing, decolonising, and reconstituting the practice of ancient history. 3. What were some of the most interesting findings you uncovered while you were researching the book? In the first place, The Tropical Turn demonstrates how a suite of economically salient crops like cotton, rice, citruses, and taro have shaped our histories, identities and landscapes. It chronicles the remarkable stories of the human movers of crops whether imperial elites or innovative farmers and how they adapted these crops to local environments. In the process, the book makes the case for a much longer history of connections across Afro-Eurasia, particularly between South Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.  The book also draws on a range of fascinating narrative and anecdotal materials. Though seemingly trivial, some of these references have the ability to engender a visceral connection with the past. I’m thinking, for example, of the ancient visitors to the temple of Athena in Lindos who, like inconsiderate tourists of the present day, displayed the compulsive need to touch an ancient cotton-embroidered linen corselet which fell apart as a consequence. The peoples of the past, like us, were varied in temperament and instinct. Some were drawn to novelty and change while others found solace in tradition and routine. The inhabitants of the South Caspian zone of Iran developed a disdain for wheat once rice was established as a staple crop. Meanwhile, one Chrusermos, a 1st century BCE physician from Alexandria, was averse to the fiery qualities of black pepper and was said to be liable to a heart attack if it were ever consumed. While tracing the grand narrative of crop migrations, I foreground these intimate encounters with past humans and their all-too-familiar fears, anxieties, desires, and aspirations. 4. How did you develop your research methodology for the book, and did it (or your feelings about it) change during the course of choosing the topic and conceptualising your approach to it, gathering the data, analysing your findings, putting all the material together and discussing it when you were writing and editing your drafts of the book, and presenting it to academic and general audiences? The Tropical Turn had a long gestation period, ultimately going back to the research I undertook as an undergraduate and postgraduate student at University College London and the University of Oxford. I had always been interested in uncovering long-distance interactions between states, societies, and cultures in ancient Afro-Eurasia. In the process of engaging with historians and archaeologists who embraced an interdisciplinary approach, it dawned upon me that the history of human mobility and connectivity could be meaningfully chronicled using biological proxies like fauna, flora, commensals, microbial organisms, and attendant diseases. There is a growing body of scholarship which has applied such bio-ecological frameworks to understand the origins and trajectory of our present condition. My training in environmental archaeology and secondary supervision under a professor of archaeobotany also significantly shaped my methodology.  5. How did you decide which case studies to focus on? The selection of case studies was guided by two main considerations, namely the availability of sources and the need to highlight a selection of different economic plant categories, whether cereals, fibres, timber, tubers, legumes, or fruits and vegetables. 6. How are human-plant and human-crop relations depicted and expressed differently among the ancient civilisations you have studied? What are some commonalities? The sheer dependence of human life on plants and animals is a similarity the ancients shared with each other but also one that we share with the ancient world. Various cultures adopted crops for a range of non-comestible purposes and endowed them with unique cultural attributes. Rice, for example, is attested in the context of a magical ritual in 6th century BCE Babylonia (modern-day southern Iraq) while citrons, a type of citrus fruit, were incorporated into the Jewish festival of Sukkot and retrospectively given a Biblical pedigree. The need to value plants beyond their basic uses is another commonality shared across space and time. 7. Do you have plans in the future to expand your research sites to include additional civilisations within and/or beyond the ancient Middle East and the Mediterranean? Which civilisations are you most interested in researching? In addition to the Mediterranean and Middle East, I also work on the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. My second co-authored book accompanied a major exhibition on ancient India at the British Museum this summer.

My own teachers continue to be the biggest research influences. The sheer breadth and depth of their learning remains inspiring. I am also motivated by a range of PhD students and young researchers across the world who continue to produce excellent work under difficult conditions. 9. Lastly, what are some of your most memorable teaching experiences at NUS? I oversaw the development of the Gilgamesh section of the curriculum for HSH1000 in the CHS programme. It is heartening to know that thousands of NUS students have now read this text and watched my lectures. I also enjoyed teaching a module on ancient diplomacy using the Amarna letters from 14th century BCE Egypt during my stint at Yale-NUS College.  Thank you very much for taking the time to answer these questions, Dr Muthukumaran, and congratulations again on being awarded Excellent Researcher! |