ZHONG SONGFA

Associate Professor Zhong Songfa (Department of Economics) recently received the FASS Award for Excellent Researcher (AER), which is presented to researchers based on the overall impact and strength of their research. The successful researcher would have “achieved consistent research excellence, produced a piece of research of great impact and be recognised by the research community as having achieved a significant breakthrough.”

A/P Zhong’s research expertise lies in behavioural economics, experimental economics, genoeconomics (a field of protoscience combining molecular genetics and economics based on the idea that financial behaviour can be traced to DNA and that genes are related to economic behaviour), and neuroeconomics.

He recently co-authored “Visceral Influences and Gender Difference in Competitiveness” (SSRN, 2019), with Dr Fu Jingcheng (NUS Department of Economics), which, through two experiments, examines the contribution of visceral influences to the difference in competitiveness between men and women.

Arising from the interdisciplinary nature of his research, A/P Zhong’s works have appeared in both economics-oriented journals such as American Economic Review, Econometrica, International Economic Review, Review of Economic and Statistics, Journal of European Economic Association and Management Science, as well as more biology-oriented ones including Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Neuron, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, and Neuroimage.

He boasts an H-index of 16 and a Google Scholar citation count of 1191. Furthermore, he has received an international sabbatical fellowship from Stanford University, is the coordinating editor of Theory and Decision (a peer-reviewed multidisciplinary journal of decision science published quarterly by Springer), was invited to be a plenary speaker at the 2018 Economic Science Association World Meetings in Berlin, and has received funding from Singapore’s Ministry of Education for two Tier 1 research grants, along with university funding of $S250,000 for his latest project, a special five year research grant on “Decision-Making: Theory, Experiment, and Application”.

1. What initially sparked your specific interest in neuroeconomics and genoeconomics? These are fairly new fields of interdisciplinary study. Could you briefly discuss them? How did you come to be interested in genoeconomics? What genomics research work have you been involved in thus far?

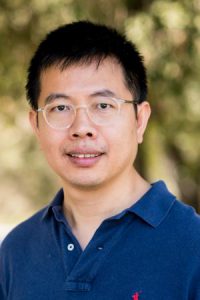

They are both interdisciplinary fields that seek to explain economic decision making from the perspective of biology. Advances in the biological sciences including brain imaging technology and molecular genetics enable researchers to peek into the ‘black box’ of the human brain and genes underlying human decision making. The ability to study how biological factors such as genes and hormones may contribute to individual variability has brought fresh impetus to research. This gives rise to the area of neuroeconomics, the interplay between neuroscience and economics, and genoeconomics, the interplay between genetics and economics.

When I was a graduate student, neuroeconomics was an emerging field. But I was not very interested in neuroeconomics, as I did not understand how it might contribute to economics. In 2007, I incidentally came across to a professor in biology working on genetics of schizophrenia. Then I started thinking about the genetic basis of economic behaviour, and initiated a research direction for my PhD thesis with my then supervisor Professor Chew Soo Hong, and Professor Richard Ebstein, a distinguished neurogeneticist at the Hebrew University. Together, we published three pioneering papers on the genetics of risk taking in 2009. In the last ten years, the field of genoeconomics has come to an understanding that we probably need to have a large sample of 100,000 to several millions in order to have more reliable results on how a particular genetic variation contributes to individual difference in economic behaviour. This is a hard constraint for me, as it requires huge resources to continue working in this field. As such, since 2011, I gradually switched from genoeconomics to a more traditional field of behavioural and experimental economics. Nevertheless, I am very much interested in working in this topic, as long as I have the access to sufficient resources.

2. In the recent study “Visceral Influences and Gender Difference in Competitiveness”, you and Dr Fu Jingcheng conducted two laboratory experiments to find out how visceral influences on competitiveness in Niederle and Vesterlund (2007)’s design differ between men and women. You found that men had more powerful visceral responses than women, which is part of the reason for the gender difference in competitiveness. You also found that a resting period would “cool off” visceral influences, and be an easy means of narrowing the gender difference in competitiveness. In your concluding remarks, you state that “lowering the aggregate level of competitiveness to achieve a gender-balanced outcome may be socially desirable in some settings” because too much competitive pressure can have negative health effects. Which settings would be ideal for using a resting period to lessen visceral influences, and thus tone down the undesirable negative impacts of competitive pressure?

This is related to a line of research that I have been interested in, namely, the role of stress in economics. Stress is ubiquitous in modern living. Notwithstanding its impact on almost all facets of modern living and the advancement made in the field of biology, stress itself has been a neglected subject of research in economics literature. In my previous study (Zhong et al., International Economic Review, 2018), we hypothesize that gender difference in willingness to compete, as widely documented since the work of Niederle and Vesterlund (2007), can be partially explained by stress response indexed by the biomarker of cortisol in the laboratory setting. After we ran the study, we were shocked to observe that we failed to replicate the known gender difference in competitiveness. We had two possible explanations. One is due to cultural difference. Another is due to experimental design difference, as we introduced a 40-minute break in order to measure the response of hormones. My recent study on visceral influences supports the second explanation, namely, gender difference in competitiveness can be partially explained by hormonal responses and can be cooled off with a rest.

In terms of more applied setting, people commonly make decisions under stress, such as hunting for a job and negotiating for salary. They may be able to make better decisions when they aware that they may be under the influence of stress. As Thomas Jefferson put it, "When angry, count to ten before you speak. If very angry, a hundred."

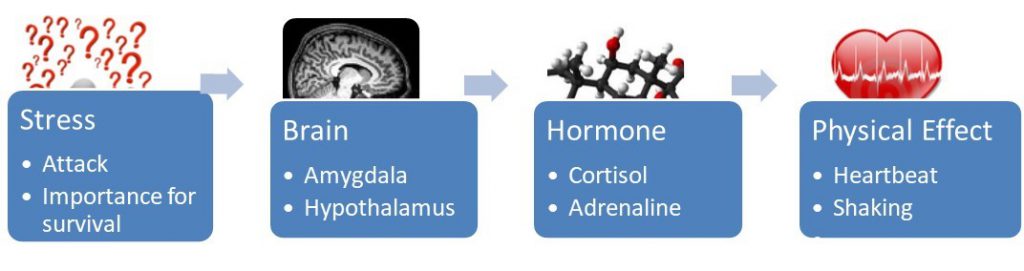

3. In the groundbreaking article “Partial Ambiguity” (Econometrica, 2017), you and your co-authors deeply examined the human aversion to ambiguity in decision making that has been demonstrated in Ellsberg’s (1961) two-urn paradox. Your study’s experiments involving different decks of 100 red and black cards had “a richer domain of uncertainty involving intermediate forms of ambiguity” rather than the full ambiguity of Ellsberg’s paradox. The implications of your findings on models of ambiguity were then analysed under three perspectives, interval ambiguity, disjoint ambiguity, and two-point ambiguity. The findings overall showed that there is a wide “range of choice behaviour which can help distinguish among various models of ambiguity under the three perspectives”. How did you and your co-authors come up with the experimental design with the perspectives of interval ambiguity, disjoint ambiguity, and two-point ambiguity?

The design of partial ambiguity came to my mind when I was daydreaming while sitting in a lecture by Professor Matthew Rabin in a summer school in behavioural economics in 2010. I cannot remember what the lecture was about, but I am pretty sure that it had nothing to do with ambiguity. Somehow I came up with the idea of partial ambiguity as intermediate cases between pure risk and full ambiguity in the classic Ellsberg paradox, and it has implications for a sense of pessimism in relation to max-min models.

4. Could you tell readers about your fellowship work at Stanford’s Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences from 2018 to 2019?

Fellows at Stanford’s Centre for Advanced Study in the Behavioural Sciences (CASBS) come from a highly diverse range of disciplines related to behavioural sciences including anthropology, economics, history, political science, psychology, and sociology, humanities, education, linguistics, communications, and the biological, natural, health, and computer sciences. The weekly seminars and lunches provided a lot of opportunities for formal and informal academic exchanges so that I got to understand behavioural sciences in a broader perspective. More importantly, CASBS is on a small hill and my office had a nice view. I enjoyed it a lot. It was a wonderful and memorable year.

5. What has been your most rewarding and/or exciting research experiment? Which of your research findings did you find most surprising and/or intriguing, and why?

I like my first three papers on genetics of risk taking behaviour, as they are among the first few studies in genoeconomics. While the implication on genoeconomics remains unclear, I find the attempt itself very exciting. I have been applying a wide range of methodologies from behavioural economics and experimental economics to genetics and neuroscience to conduct research on decision making. My work may perhaps be considered “too diverse”. I like the parable of the blind men and an elephant. It is a story of a group of blind men who have never come across an elephant before and who learn and conceptualize what the elephant is like by touching it. Each blind man feels a different part of the elephant's body, but only one part, such as the side or the tusk. They then describe the elephant based on their limited experience and their descriptions of the elephant are different from each other. The beauty of doing interdisciplinary work is to look at the same question from different perspectives and offer explanations at different levels.

6. Could you discuss your plans for a future research study or studies?

While I hope that I can find something more interesting in the future, for now, I spend a lot of time thinking about the notion of karma from a behavioural perspective.

Thank you very much for taking the time to answer these questions, A/P Zhong! Also, congratulations again on being awarded Excellent Researcher!