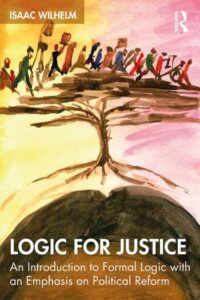

ISAAC WILHELM

Dr Isaac Wilhelm is an Assistant Professor at the NUS Department of Philosophy and a Presidential Young Professor. He obtained his PhD in Philosophy from Rutgers University, New Jersey, where he also got an M.S. in Mathematics. His research interests include metaphysics, philosophy of science, and philosophy of physics. Dr Wilhelm teaches courses on feminist philosophy, logic, and epistemology. His current projects center on non-fundamental phenomena that have objective and subjective characteristics. One deals with centered propositions: their chances, their naturalness, and their relevance for rationality. Another develops a unified theory of explanation in metaphysics, science, and social philosophy. |

|

Dr Wilhelm was recently granted the FASS Award for Promising Researcher (APR). This award is presented to researchers who have produced research that shows potential impact and promise. We congratulated Dr Wilhelm and spoke to him about his research work. |

|

1. What inspired you to become a philosophy professor after working in documentary filmmaking and tutoring?  I was drawn to the breadth of topics that philosophy covers, and the way in which it covers them. Philosophy often has the real-world connections that documentaries have — take philosophical questions about values, ethics, and rationality — as well as the formal rigor that math has — take philosophical questions about logic, science, and the nature of argumentation. So in that sense, philosophy occupies a kind of middle ground between documentary filmmaking and the tutoring/mathematics that I’ve done. |

|

2. Given your background in documentary filmmaking and your study of cinema, would you be interested in teaching or researching philosophy of film? Which films would you show to your students as part of a course on film and philosophy?  I absolutely would! For some reason, I’ve never been entirely satisfied with the philosophy and film papers, and film course syllabi, that I’ve written. But I should probably get over that, and just design a course and/or publish some papers on philosophy and movies. Here are some movies I’d show in a course at NUS: “The Lonedale Operator” (Griffith), “Man with a Movie Camera” (Vertov), “City Lights” (Chaplin), “M” (Lang), “I was Born But…” (Ozu), “Singin’ in the Rain” (Donen, Kelly), “Stagecoach” (Ford), “The Searchers” (Ford), “Vertigo” (Hitchcock), “2001: A Space Odyssey” (Kubrick), “After Hours” (Scorsese), “Beau Travail” (Denis), “The Mission” (To), “Joint Security Area” (Chan-wook), “Punch-Drunk Love” (Anderson), “Inglourious Basterds” (Tarantino), “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night” (Amirpour), “Certain Women” (Reichardt), “Little Woods” (DaCosta), “Judas and the Black Messiah” (King). All of these movies are, in some fundamental way, about seeing, through your own perspective and through someone else’s. There’s lots of interesting philosophy to be done on them. |

|

3. How does your additional academic background in mathematics complement your work in philosophy?  Mathematics helps me formulate clear, rigorous versions of various interesting views. Measure theory can facilitate the formulation of rationality principles, for instance; and group theory can facilitate the formulation of metaphysical accounts of structure in physics. Mathematics is such a beautiful, clear language — it often provides a great litmus test for the degree to which an idea has been worked out. Sometimes, however, recasting philosophical ideas in mathematical terms can distort the core of those ideas, and lead to confusion or misunderstanding rather than clarity. It’s a balancing act: using mathematics in philosophy is often, though not always, a sound strategy for getting clear on various issues. |

|

4. What are the most interesting and/or challenging aspects of your current research projects, such as your study on centered propositions, and your work developing a unified theory of explanation in metaphysics, science, and social philosophy?  Centered propositions are propositions which get expressed by sentences like “I am a philosopher,” that is, sentences featuring indexicals like “I”, “here”, and “now”. One of my research projects uses linguistic accounts of that vocabulary’s syntax and semantics to propose theories of agent-relative fundamental physical laws — in certain versions of quantum mechanics, for instance, or in certain cosmological theories — which avoid problems that other proposals face. Part of this project also engages with the interaction between centered propositions and epistemological principles, logical principles, and even the most complete fundamental description of reality, which I suspect must use indexical expresses like “I”: and this suggests that there’s a hard-to-pin-down-precisely, but unavoidably fundamental, subjectivity in reality. |

|

5. How do you approach teaching feminist philosophy? What are some of the ways that men can benefit from learning feminist philosophy?

My approach to teaching feminist philosophy is roughly this: strike a balance between (i) listening to others, since my students’ experiences are often very different from mine, and (ii) guiding others, since my students generally don’t know as much feminist theory as I do. One of my main goals is to help students better understand both their own thinking about feminist issues, and also the thinking of others with whom they might disagree. Another goal is to help students work through their experiences, and the experiences of those around them, by using feminist ideas. |

|

6. You have a stunning publication record. How did you manage to write so many high quality papers, as well as an entire book, in such a short time? Are there any techniques you would recommend to those who are seeking to write both faster and better?

|

|

7. Which philosophers have been most influential for you?

There are so many philosophers that I could, and probably should, mention here. My absolute favorite philosophers are probably Plato, David Hume, Nelson Goodman, and David Lewis. In my view, the best philosophers have a talent for (i) articulating ordinary, basic views which many of us have about the world, and (ii) showing what the surprising, challenging consequences of those views might be. Plato, Hume, Goodman, and Lewis, do that quite well. They’re good at ‘following through’ on their own commitments, in the sense that they do a better job than most anyone at unearthing the surprising views to which their various initial, starting commitments lead. |

|

8. Lastly, what has been your most memorable teaching experience at NUS? There are too many memorable teaching experiences to count! The students here are fantastic: I’m constantly impressed by their intelligence, thoughtfulness, work ethic, and diligence. One particularly memorable experience occurred in feminist philosophy a while ago. During discussion, a student brought up her experience of attending a single-sex school in Singapore. Immediately, other students started sharing about their own experiences in single-sex schools and co-ed schools. An extremely interesting and lively discussion unfolded, in which everyone weighed the pros and cons of attending schools that are single-sex versus attending schools that are co-ed. I learned a ton, myself. And now, my feminist philosophy course devotes a week to this topic, in which we read work by people at NUS, NTU, MOE, and other Singaporean institutions, about the advantages and disadvantages of single-sex schools. |

|

Thank you very much for taking the time to answer these questions, Dr Wilhelm, and congratulations again on being awarded Promising Researcher! |

Dr Wilhelm has already published 23 papers, with 19 in tier-1 journals and four in top-five journals. This is comparable to what the NUS Department of Philosophy calculates is acceptable to receive tenure four times over. His first book,

Dr Wilhelm has already published 23 papers, with 19 in tier-1 journals and four in top-five journals. This is comparable to what the NUS Department of Philosophy calculates is acceptable to receive tenure four times over. His first book,

Writing is super, super hard. I was terrible at it in college, and I still have so much to learn. One thing that helped me, a lot, was to find some good writing role models. People like George Orwell, William Faulkner, and Virginia Woolf, are excellent writers. Now, their more experimental, boundary-pushing work — though rightly famous — is also not very helpful when you’re trying to learn how to write clearly. But their non-fiction essays — like Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant,” say (with apologies for some of Orwell’s language) — are so brilliantly simple, clear, accessible, and powerful. If you’re interested in learning how to write better, and thereby how to write faster, I’d recommend reading a lot of Orwell; and bell hooks, for that matter.

Writing is super, super hard. I was terrible at it in college, and I still have so much to learn. One thing that helped me, a lot, was to find some good writing role models. People like George Orwell, William Faulkner, and Virginia Woolf, are excellent writers. Now, their more experimental, boundary-pushing work — though rightly famous — is also not very helpful when you’re trying to learn how to write clearly. But their non-fiction essays — like Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant,” say (with apologies for some of Orwell’s language) — are so brilliantly simple, clear, accessible, and powerful. If you’re interested in learning how to write better, and thereby how to write faster, I’d recommend reading a lot of Orwell; and bell hooks, for that matter.