Return to Civil War: Insurgent Groups and the Decision to Abandon Peace

January 19, 2023

Professor Jacques Bertrand, 2023 LKC NUS-Stanford Fellowship awardee, is visiting FASS from 11 January to 12 April, 2023. He is working on Return to Civil War: Insurgent Groups and the Decision to Abandon Peace, a research project and book that examines the evolution of insurgent groups during and after conflicts.

Professor Jacques Bertrand, 2023 LKC NUS-Stanford Fellowship awardee, is visiting FASS from 11 January to 12 April, 2023. He is working on Return to Civil War: Insurgent Groups and the Decision to Abandon Peace, a research project and book that examines the evolution of insurgent groups during and after conflicts.

We interviewed Prof Bertrand, who teaches in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto, about his study.

1. How did you becoming interested in studying how insurgent organisations have evolved during and following wartime?

My work over the last decade has largely focused on groups and movements that seek autonomy or secession from states in Southeast Asia. Recently, I published two books that are related to these themes. The first, Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia (Cambridge UP), addressed the question of whether and how periods of democratic rule in Southeast Asia have helped reduce conflict between states and groups seeking such autonomy or independence. It was comparative, and looked at such movements in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand. Just this year, I also published a book focusing exclusively on such groups in Myanmar, which has a very large number of minority ethnic groups seeking a reinvented federal state or independence.

The book, Winning by Process (Cornell UP), looked at the period of semi-democracy and relative openness from 2011-2021, and takes stock of what impact this period had on resolving the long standing civil wars in Myanmar, culminating in an assessment of the implications following the coup in 2021. So, much of this research was focused on understanding the circumstances that make conflict worsen, or get better, particularly in relation to changes in the state, at times when there are more democratic institutions in place and better possibilities for peaceful outcomes.

In doing this research, however, it became obvious that insurgent groups are quite different from one another, and their responses to changes occurring at the state level can be quite different. This observation, combined with set of fortuitous circumstances, made me pivot toward thinking about how these groups evolve in peace time and the legacies from war. The research is framed in relation to debates about civil war, with more recent work suggesting that most civil wars are recurring ones, so part of the puzzle is to understand what about the groups themselves, their strategies and capabilities, constrains or prompts them to return to war, or follow different peacetime trajectories. The topic became exciting for me in part because of a new teamwork approach that I developed, where I am now leading a team with a colleague who focuses on large-N studies of civil war, another who is also a Southeast Asianist, and a team of several doctoral students at the University of Toronto who are working on various aspects of civil war in Southeast Asia. We obtained funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the United States Institute of Peace. This is a new exciting direction for me to build such a team, which constitutes the core of our newly created Post-Conflict Reintegration Lab (Postcorlab.com).

2. What makes Southeast Asia a fruitful site to study the characteristics and behaviour of insurgent groups?

Southeast Asia has had an unusually high number of such insurgent groups. Of course, Myanmar alone has a bewildering number of such groups, which is partly explained by the unfortunate history of failed state building early in its history, but also because of subsequent strengthening of ethnic identity as a core principle of state organization. With so many different ethnic groups holding strong historical grievances against the Myanmar state, it is therefore not entirely surprising that many groups were formed and have engaged in civil war in Myanmar. But it’s also the case that such groups have been strong in the region more broadly, in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines as well, for instance. As I explain in a Cambridge Elements book that I am just finishing on nationalism in Southeast Asia, the region’s strong anticolonial nationalist movements in the first half of the twentieth century had both positive and negative outcomes. On the positive side, they allowed some bottom up but also entrepreneurial nationalist leaders to unify resistance movements against colonial rulers but, most importantly, to create some common bonds and form states in a region that is much more diverse than many other parts of the world. But, on the negative side, such nationalist projects in newly independent states combined with Cold War confrontation and authoritarian regimes created stronger boundaries and limits to the inclusiveness of previous nationalist ambitions. As a result, some groups became not only marginalized and excluded, but often strongly repressed or subjected to assimilationist policies, which laid the foundations for these alternative nationalist movements to arise and often express themselves through insurgent organizations. As a result, Southeast Asia has a large number of insurgent organizations, diversity of regime types and historical experiences with the colonial past that makes it a very important site to understand these groups and civil war more broadly.

3. What areas of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand and/or Myanmar are you and your research team planning to focus on?

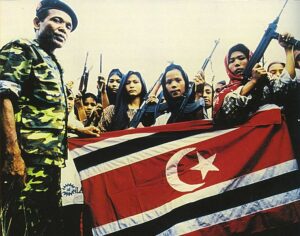

We are particularly interested in understanding and comparing groups whose trajectories have included periods of sustained peace, with some that returned to war. We want to better understand the strategic decisions that make groups invested in peace periods. When we look carefully at groups, for instance in Myanmar, we realize that there is a broad range of groups from some that are small, relatively disorganized, and with only a handful of soldiers not very well tied to local communities; and others that are large, provide extensive services to communities in territories they control and basically act as local governments. We think that this variance in the types of groups will reveal important dimensions of how and why some groups adhere to peace more than others. In order to capture some of these distinctions, we are focusing on groups along the Thai-Myanmar border in the first instance (the Karen National Union, Karenni National Progressive Party, Restoration Council of the Shan State, New Mon State Party) and hope that we might be able to regain some access to the Kachin Independence Organization if the political situation changes in Myanmar. In Indonesia, we want to better understand how the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) was able to manage its transition to a political party and local government. Finally, we are studying the Moro Islamic Liberation Front’s current transition as the new Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) begins to be implemented. So, our team will be going to Mindanao, Aceh, as well as the Thai-Myanmar border in particular.

4. What challenges do you expect to encounter when carrying out your fieldwork in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand and/or Myanmar?

Lots of them. Fieldwork in Myanmar is not possible right now. So we are dependent on gaining access to insurgent groups who maintain offices and hold meetings across the border in Thailand. This is not obvious. We anticipate that fieldwork in the Philippines will be much easier. There is a lot of excitement and enthusiasm about the new peace agreement and the BBL. I think many people will be eager to share their experience. We hope that the same will be true in Aceh, although GAM is now almost a distant memory since the 2006 agreement. This is good news! But can be a challenge for research on how the organization transitioned. But it is all part of what makes academic research useful and interesting.

5. What commonalities do the insurgent groups in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Myanmar that you are studying share?

The main commonalities among insurgent groups in all these groups is that they are nationalist in their orientation, in that they claim representation of an alternative nation, based on ethnic distinctions, and seek some form of greater recognition for self-determination in territories under their control. They are usually seen by states as highly threatening, because they are perceived as secessionist. But the reality is that, beneath the veneer of pro-independence movements, most of these groups are actually seeking some compromise within the state, usually some form of autonomy, in recognition of historical grievances and to be governed in ways that acknowledge their differences or their way of life. Beyond that, they are quite different, with some being much less representative and with few ties to local communities, while others enjoy a high degree of legitimacy as representatives of their respective ethnic minority group. Coming back to what I mentioned above, these characteristics that are common among insurgent groups in Southeast Asia, are actually quite distinct from many insurgent groups when comparing to those involved in civil wars in other regions of the world. When expanding that scope, we see that insurgent groups with such nationalist orientations and seeking this kind of autonomy is actually not that common in other regions of the world.

6. To what extent do you think ASEAN can promote democracy in conflict-affected regions of Southeast Asia?

To begin with, ASEAN would need to be better at promoting democracy among its member states. Democratic backsliding has occurred everywhere in recent years, and also in Southeast Asia. While there are occasional glimmers of hope, even Indonesia and the Philippines have regressed in recent years. The mind-set needs to change regarding the claims and grievances of conflict-affected regions. It does not help to frame the issues as “terrorist”. ASEAN can play some role in fostering exchange of views and ideas regarding how some of the grievances, and experiences of members states, show progress toward reimagining the way things are done in Southeast Asia. Indonesia still shuns federalism in principle but, in practice, the experiment in Aceh is fascinating for the degree to which it represents a model of asymmetric federalism that goes beyond many established federal states. What is evolving in the Philippines is interesting to watch in this respect as well. While ASEAN’s own way of doing things, and sensitivities, prevent it from taking much of a leadership role, or even an active one within states, perhaps a forum to address some of the lessons from those members countries might be possible. But even this might be too much for the ASEAN way.

7. What are some possible strategies that policymakers could utilize to reduce nationalist conflicts in Southeast Asia?

A first step would be recognizing that many of the conflicts out there are based on actually sound sets of grievances. Conflict regions in Southeast Asia often express peoples’ long lasting experience of being repressed by the state, subjected to discrimination and marginalization, displaced, neglected, and subjected to human rights abuses. War, violent repression, attempts at assimilation, or highly centralizing policies have all failed to reduce violence and conflict. The most promising models are starting to show the benefits of adopting institutions that recognize difference and empower to some degree nationalist/ethnic groups in various forms of regional or local autonomy that can allow them to address the most important issues for their communities. International or regional actors, to the extent that a role might be allowed, can provide some help in designing or thinking about effective local strategies. Of course, solutions ultimately can’t rely on external models; they will come from contextually-sensitive crafting that might obtain some inspiration from what has worked elsewhere. More specific to my current project, we are hoping to develop ideas regarding the role that multilateral organizations might play to strengthen insurgent groups’ buy-in of peace during war-to-peace transitions but these ideas will come after our research has gone further. So, more next time!

Thank you very much for taking the time to share your research with us, Prof Bertrand! We wish you success in your studies in and beyond Southeast Asia!