Clones, Drones and Visual Culture: Teaching the Human Condition in the 21st Century

April 16, 2024

IN BRIEF | 5 min read

- Associate Professor Graham Wolfe and Assistant Professor Beryl Pong incorporate innovative pedagogical tools into their lessons to get their students to think critically about pertinent issues of the day.

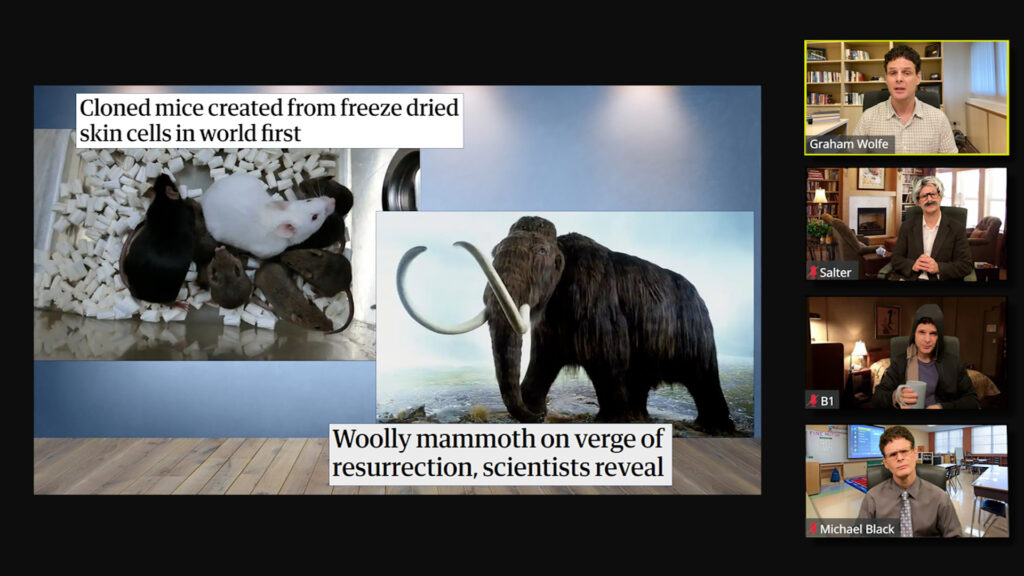

As far as Zoom lectures go, it was nothing special. The only recognisable face on the screen was his own, as Graham Wolfe, Associate Professor in Theatre and Performance Studies, spoke to a virtual audience of hundreds.

But then a sense of the uncanny set in as three other Graham Wolfes joined the Zoom call. One, smartly dressed and smiling, responded enthusiastically to what the first Graham Wolfe was saying. Another, older and with a moustache, listened to the lecture with concern. The third, a thuggish and hooded figure, snarled disdainfully from his Zoom box, occasionally interrupting and criticising the first Graham Wolfe’s ideas.

Soon it became clear that all three of these new Graham Wolfes were characters from the play that Assoc Prof Wolfe was discussing, Caryl Churchill’s A Number, which examines the ethics of human cloning and identity.

“Thumbs-up” and “clapping” reactions from the students cascaded across the screen. Students comment that his impersonation of various characters, and the interactions between them on Zoom, provoke them to think critically from a range of perspectives.

“I’m hoping students feel, just for a moment, like they’re watching the impossible,” said Assoc Prof Wolfe, who had tried to explain the concept of the uncanny in an equally uncanny manner. Most of his teaching is in Theatre and Performance Studies, but he is also a guest lecturer for HSH1000: The Human Condition, an integrated humanities module that is part of the common curriculum for students at the NUS College of Humanities and Sciences (CHS).

At the Department of English, Linguistics and Theatre Studies, the medium is just as important as the message. For Assistant Professor Beryl Pong, who teaches an honours-level literature course titled Topics in Cultural Studies: Drone Aesthetics, that medium can even include the most unlikely subject of inquiry in a humanities classroom: video games.

But it’s not all fun and games. When students decimate an entire village (virtually, of course) at the click of a button, this points them to a larger revelation – that the gamification of drone warfare has desensitised drone operators to the suffering they inflict.

As Asst Prof Pong puts it: “Humanities and the arts are not just an add-on to understanding society or to hard questions about science. They mediate complicated issues, and looking at them critically helps us to see these issues more clearly.”

Out of the Box

Assoc Prof Wolfe knows that Zoom classes can feel just as “claustrophobic” for the teacher as they do for students, which is why he challenged himself to think out of the box – literally – to deliver lectures that would stick. And what better way to teach a play than to act it out?

Decked out in different costumes, he doubles, or triples, as different main characters. It is not merely a way for students to experience how the plot and dialogue play out on stage. After he and his clones act out a scene, the characters return as “guests” to discuss the assigned class readings with each other in a meta talk show.

Wacky as the whole set up is, he has a more profound hope for his students – that they will be more conscious of the frameworks through which they perceive things. Students comment that his impersonation of various characters, and the interactions between them on Zoom, provoke them to think critically from a range of perspectives.

“To a large extent, whatever I talk about is going to be filtered through Zoom. No matter how exciting an idea I raise might be, I’m still raising it within that little box,” he said. Similarly, the ways in which people perceive the world are sometimes filtered through structures, conventions or expectations that they are not necessarily conscious of.

Human perception is never objective, and existence is never singular. These are perennial concerns tackled by the humanities, and which he hopes science majors in the cohort might find useful in their own fields. “Doctors are much better doctors if they’ve studied the humanities,” he added.

Plays and Playfulness

As with any performance, it takes a whole lot of dress rehearsals to pull off Assoc Prof Wolfe’s self-cloning technique – as well as the tech know-how. The former was something he is accustomed to, the latter not so much, considering that he never owned a smartphone with an Internet connection until the pandemic struck.

“I couldn’t even donate it to Singtel because it was too old,” the Canadian, who joined NUS in 2012, said with a chuckle. Out of sheer necessity and boredom during the pandemic, he familiarised himself with the world of green screens and editing software.

“It doesn’t have to be Hollywood quality. Theatre is usually a little bit rough around the edges…Part of the effect is that it’s just a guy with a camera playing around, and that might make the self-cloning even more useful than if it were professional,” he explained.

Ultimately, he wants his students to have fun learning.

As the German playwright Friedrich Schiller once said, human beings are only fully human when they play. Assoc Prof Wolfe is a strong proponent of the value of play and comedy in learning, especially when people have the misconception that literature and theatre are ‘stuffy’ topics.

“I think people can be learning in powerful ways when they’re laughing,” he said. “It’s not just about occasionally injecting a joke to lighten the mood before getting back down to ‘serious thinking’. People laugh sometimes when their expectations have been overturned, or when their normal frameworks have been challenged.”

‘Close reading’ of Technology

The utility of play is featured in Asst Prof Pong’s class too. It is not every day that students get to play video games for class. But her syllabus dedicates a week to two indie video games which dissect the aesthetics and ethics of drone warfare.

In Unmanned, for instance, students inhabit the role of a drone operator. Players follow him through his mundane everyday routine of brushing his teeth, shaving, pressing a few buttons at work, then having a post-shift drink with colleagues – only to repeat it all over again.

More office workers than military personnel, drone operators in real life are often derisively referred to as “cubicle warriors”. This raises ethical concerns about the asymmetry of drone warfare, in which operators seem to be “manhunting” unsuspecting victims from a safe, remote location via a screen.

Tracing drone technology is Asst Prof Pong’s take on the wider field of cultural studies. Despite its roots in violence, drones have proliferated in popular culture and everyday life, including in filmmaking and recreation.

“I wanted to pick a technology whose developments are still changing as we speak…we don’t have a throughline that connects all its uses, which involve very different ethical questions,” explained the Canadian, who joined NUS in 2021 and is also a UKRI Future Leaders Fellow at the University of Cambridge.

Instead of beginning with theories in the field, she starts with real-world applications. “One of the things my students like to ask is, ‘What is the real-world utility of literature?’ My experiment with this course is that we’re not only looking at literature, but we’re close reading this technology, looking at the way its “forms” relate to the socio-political issues of our time.”

It is not just games. Every week explores different mediums, from visual art to popular media such as Twitter fiction and even an episode from the hit Netflix series Black Mirror.

For literature students accustomed to poetry and novels, it is not always easy to introduce them to non-text-based media, but Asst Prof Pong’s advice is to simply approach it like they would any other text.

“By encouraging us to look at the products of pop culture through a critical lens, Dr Pong showed us that culture surrounds us all,” Kevin Khoe, an English Literature student from a previous iteration of the module, said. “Just evaluating the shows we watch and games we play unveils so much about the subtle cultural energies, beliefs, and practices that influence our lives.”

It is such explorations beyond the typical that

“The most satisfying part about teaching this course is also the most challenging,” she said. “It’s helping students leave their comfort zone and take risks with what they study and write about.”

Thought Experiments

While literature courses typically require a final essay, Asst Prof Pong’s students have the option of submitting an “un-essay”— a creative work in any medium – that reflects critically on class material.

About half to two-thirds of the students choose to do the un-essay. That in no way means taking the easy way out – students are still graded on their thesis, analysis, and clarity of thought. They also have to submit a short write-up to explain their thought process and how their work relates to critical concepts learned over the semester.

In fact, the creative assessment arguably requires more effort. For instance, Kevin hand-carved a tribal drone motif on a plank of olive wood that he ordered from Carousell – symbolising how much drones have been inscribed in people’s lives, resulting in them having to navigate a culture with machines constantly hovering above and surveilling them.

“In the study of literature, we deal with abstract topics [and] the conceptual world of ideas and language,” he mused. “Working on the un-essay was a refreshing opportunity to exercise my intellectual energies through a tactile and visual medium.”

At the end of the day, Asst Prof Pong’s pedagogical rationale is simple: “I want them to do things not just for a good grade, but because it’s a question that bothers them and they want to answer it.”

From clones to drones, the question of human ethics and morality is a never-ending rabbit hole of inquiry. Luckily, these professors know just where to start.

This story first appeared in NUSNews on 16 April 2024.