Unsettling: Chinese International Graduate Women Navigating (Im)mobility and Chrononormativity

April 3, 2025

Prof Fran Martin, Professor of Cultural Studies and co-convenor of the Asian Cultural Research Hub at The University of Melbourne, gave a talk titled ‘Unsettling: Chinese International Graduate Women Navigating (Im)mobility and Chrononormativity’ on Tuesday, 1 April 2025, jointly organised by the NUS Department of Communications and New Media and the NUS Asia Research Institute. She spoke about the final phase of her long-term research project examining the experiences of female university graduates from China, which features interviews with 34 Chinese women ranging from ages 26 to 38 who are graduates of Australian universities. Through them, Prof Martin explores the concept of “settling”, which notably has a double meaning – the first, settling down and prioritising a domestic life as opposed to moving house and changing jobs or schools, prioritising a career- and experience-driven life, and the second, settling for a life (or person) that is safer, more traditional, and family-oriented, and less exciting.

The study began in 2012 as a Pilot where Prof Martin carried out in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 15 female University of Melbourne graduates. The second phase of the study ran from 2015 to 2021 and was an ethnography of 56 participants, six of whom continued from the first phase. The participants were followed on their journeys from China to Melbourne with multiple interviews, informal conversations and hangouts, and group activities that allowed for participant observation. This was followed by the third and final phase from 2023 to 2024, which included two rounds (in Australia and China) of supplemental interviews with 34 of the participants.

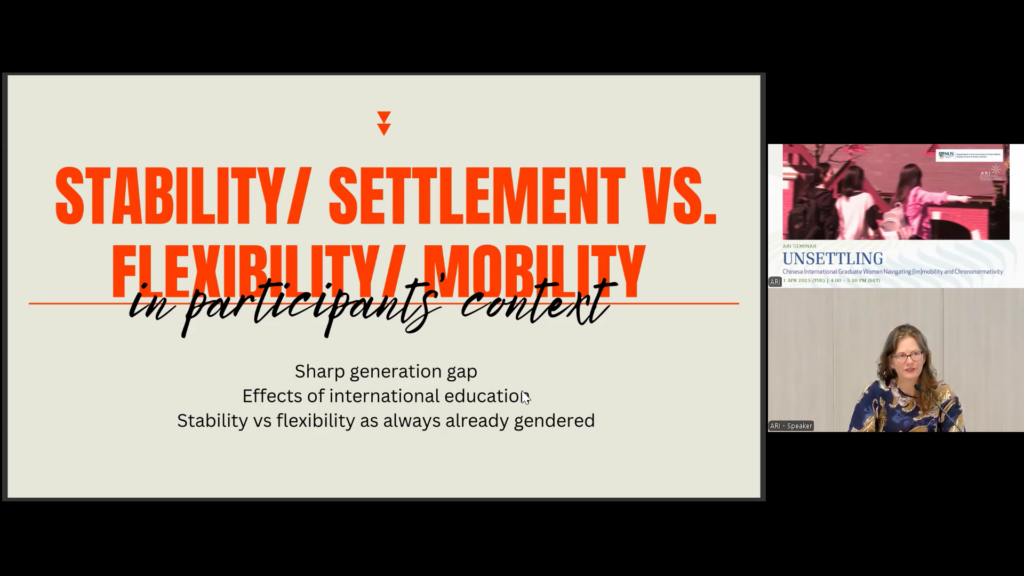

Drawing on migration, mobility, and sociology of youth transitions studies, Prof Martin’s research project focuses on the tension between stability/settlement and flexibility/mobility. She examines the generation gap, the role of gender, and the effects of international (Western) education in her analysis of her conversations with the participants. The women characterised the idea of “settling” in multiple ways; as having an established professional career, having a fixed, long-term home, as indicated by institutional markers such as Permanent Resident status, hukou (household registration in China), or property ownership, as a psychological state free from anxiety and uncertainty, as establishing a family, or their own financial independence.

Prof Martin found that the participants had diverse and ambivalent experiences, and reported that they had to negotiate intensified internal and external pressures to marry, that they re-evaluated their formerly negative impression of their married cousins and acquaintances who opted to remain in or move back to their small-town hometowns, that they faced challenging decisions about whether to pursue safe and stable positions or higher profile professional careers where they risked being “optimised” (made redundant), that they lost social connections due to their frequent domestic and international relocations, and that after graduating felt overwhelmed by too many possibilities, difficult decisions, and the loss of clear goals and former passions. This ambivalence carried into their conceptualisation of “settling down”, where they wondered if it was time to settle down, if they were already settled down, if they wanted to settle down, if settling down was a goal worth striving for or a disappointing compromise, if settling down was even possible, if settling down was a state of mind as well as a geographic or temporal condition, and how to tell if they had indeed settled down.

Prof Martin pointed out that these Chinese graduate women’s situation of feeling torn between stability and settlement versus flexibility and mobility reflects the situation of other youth around the world in our current “age of uncertainty”, but with, as she puts it, “(trans)national-contextual specificities” – the interplay of global trends with contextual specificities. She also remarked that the temporal dimension of the concept of “settling down” is markedly gendered and recommended that the research be furthered by examining the extent to which return student migration contributes to social transformation within China. Prof Martin additionally asserted that our understandings of the role of emotions in migration scholarship can be extended by looking at the emotional intensity of people’s lived experiences of unsettlement. The talk was followed by a vibrant discussion where both in-person and remote attendees asked about the participants’ sense of belonging to the cities where they were living, their socioeconomic class dimensions, and their sense of regret, among other topics.

A report on the study, ‘Unsettling: Chinese international graduate women navigating compulsory flexibility and gendered chrononormativity’ (Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Mar 2025) can be accessed here. More information on the seminar is available here.