A Marriage of Analysis and Abstract Concepts to Enrich the Learning Experience

June 21, 2024

IN BRIEF | 10 min read

- NUS College makes teaching and learning analytical skills more enriching through abstract but relatable concepts like emotions and relationships.

Keeping students engaged in a class when teaching technical subjects or abstract concept can be a challenge for educators. The right framework, however, can transform the learning experience from one of boredom to an ‘eureka’ moment that opens students' eyes to new possibilities.

At NUS College (NUSC), the honours college of NUS, where creative and innovative teaching methods are encouraged, some lecturers have found success in using abstract but relatable concepts to teach analytical skills.

Three courses employing this approach tap on common elements of the human experience – emotions, interpersonal relationships and personal identity – to both engage the students’ interest and demonstrate how analytical skills can be applied to a variety of domains and not just to tackle purely scientific questions.

Identity, Death, and Immortality

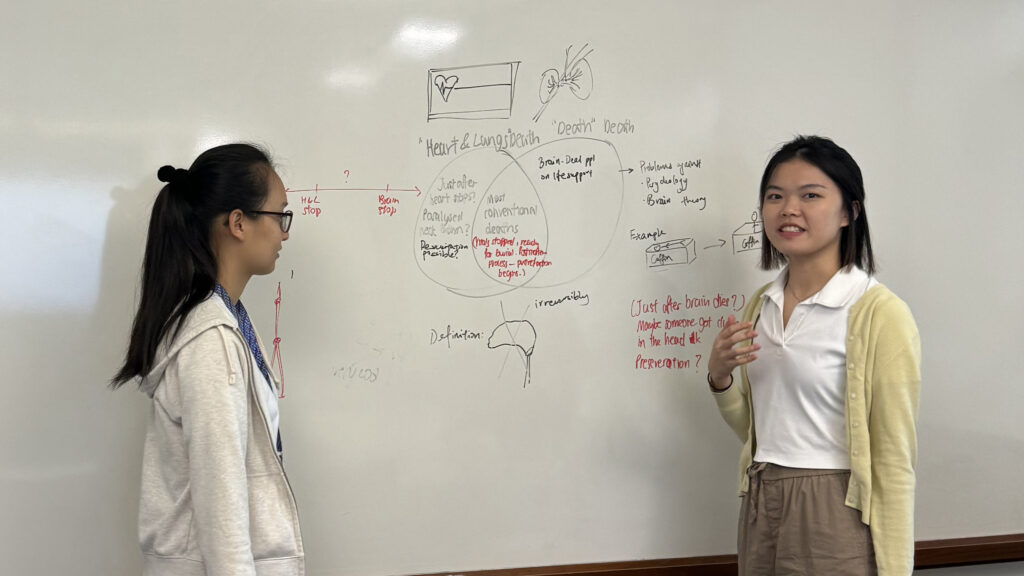

What makes you who you are, what happens after death, and can we achieve immortality – these questions have confounded humanity for millennia, but students of Dr Jane Loo’s writing course “Identity, Death, and Immortality” will try to answer them in their quest to learn the skill of academic writing.

The course starts with the concept of personal identity, which is teased out for each student through a series of thought experiments, and moves on to how their take on the concept affects each individual’s views of death and immortality. Students take on an interdisciplinary approach as philosophy and science intertwine in the lessons, with equations used to map out cause-and-effect relationships and technologies such as artificial intelligence and cryopreservation weighed for their potential to facilitate life after death.

The humanities and sciences are both integral to the discussion of these topics, says Dr Loo, whose background is in metaphysics, a branch of analytic philosophy. “If you talk about personal identity without the science, it’s not realistic. The psychological and physical theories of personal identity all have science and philosophy in them, going hand-in-hand.”

The universal nature of the topics prompts lively discussions, since every student has a unique perspective to contribute, and highlights the importance of structuring and presenting one’s argument well, said first-year computer science major Celes Chai. “Because everyone has encountered (each concept) and can talk about it, the difference is how we talk about what we think about it,” she explained.

At the same time, the personal stakes turn the discussions and writing assignments into exercises in tact and sensitivity, as the students quickly realise that one person’s basis for their theory of personal identity can be a sharp contradiction to someone else’s beliefs.

Celes observed: “When we’re talking about other people’s writings – for example, poems, stories, films, or movies – people have their opinions, but they don’t feel so strongly about them. But when you’re talking about personal identity, the way you phrase something can be hurtful to someone else if you’re not careful.”

Nevertheless, the emotional threads running through the subject matter presented an opportunity for first-year student Emma Tan to employ pathos, or appeal to emotions – a persuasive device that she had not thought appropriate to use in an academic paper before.

“Initially, I wanted to remove all emotion and be as objective as possible, yet I found that some arguments that I truly believed and felt would be convincing were those that appealed to one’s emotions,” said Emma, who is pursuing a double major in psychology and business management. “As such, leaving it out would make the paper too objective and lacking in a human voice – or in a way, written by a bot.”

Dr Loo hopes that her students will gain not just the skills to write solid and well-reasoned academic papers, but also a healthy appetite for exploring and debating anything that interests them, no matter how abstract it is.

“Be open to possibilities and things that don’t happen in the real world,” she said. “As long as there are no outright contradictions, nothing that is logically impossible, it’s okay to talk about it.”

Moral Emotions in Everyday Life

Emotions are often dismissed as incompatible with good decision-making, with objectivity and logic touted as the superior policy. While there is value in seeking a balanced view of any issue, the idea that decisions should not involve emotions begs the question: Is it even possible to divorce ourselves from our emotions and be truly objective?

Dr Bart Van Wassenhove’s course “Moral Emotions in Everyday Life” challenges this notion and presents a methodical approach that treats emotions not as inconsequential and undesirable in decision-making, but fruitful for analysis, yielding insights into the morals and motivations behind our thoughts and actions.

“Even if you are committed to being objective, you need to be attuned to emotion to understand why people are disagreeing with you and why they feel strongly about an issue,” said Dr Van Wassenhove.

“But I also think we are often fooling ourselves when we think we’re being objective. There is emotion driving us and we often are not aware of it. I would always encourage people to think carefully about if things are actually devoid of emotion and impartial – and also whether impartiality has downsides, potentially.”

The study of each emotion in the course starts with identifying their characteristics in a handful of categories, such as the factors that elicit the emotion and what actions it usually leads to. This enables students to differentiate related emotions like guilt, regret, and remorse, and compare psychological, philosophical, and personal perspectives of each one. Each topic is rounded out with a film that illustrates the emotion playing out in realistic situations – for instance, how anger is expressed in the racially tense events of Spike Lee’s film Do the Right Thing.

Elren Chae, a second-year biomedical engineering major who wanted to better understand the many emotions she experienced when moving from South Korea to Singapore for university, said the course gave her a useful framework to guide her interactions with others and dive deeper into specific emotions that interest her.

“I don’t have all the answers to what I’m feeling now, but I know how to ask questions that would help me organise my thoughts,” she said. “And when I ask those questions, the goal is not to find an answer but to elucidate the situation and comprehend it in my own terms.”

Dr Van Wassenhove’s approach also validated how final-year student Rishabh Anand naturally thought of emotions as a computer science major – while abstract, they could still be broken down into simpler components that combine in various configurations to form complex emotions. His main takeaways from the course were the surprising realisations about human behaviour, including his own, that emerged along the way.

For instance, identifying an element of fear in his reactions to certain research questions and not to others, even though they all piqued his curiosity, helped him to realise when he was feeling awe or wonder and predict whether his interest would be sustained or fizzle out when he started researching a question.

“It was a very fun class, as a mind-bending sort of exercise. Sometimes it would reinforce the way I think and I’d walk out saying ‘Ah, so I was correct all along.’ But then there were other days where I learned something new and added it to my mental model,” Rishabh said.

In Search of Soulmate

The course “In Search of Soulmate” teaches quantitative reasoning and analysis through the framework of the search for a romantic relationship. Students study existing research on questions of love and relationships, and then conduct their own research – from formulating the research question, to gathering the data, to analysing it and comparing their results to the existing literature.

When designing the course, instructor Dr Chan Chi-wang looked for a ‘Trojan horse’ topic – something exciting with enough scope that he could pack into it all the concepts and technical skills he needed to teach. Most people have a natural interest in seeking out and strengthening interpersonal relationships, making this topic an ideal choice.

Finding enough existing research to build out the course curriculum was challenging, but the dearth of research on the topic also provides plenty of opportunities for students to discover new insights, Dr Chan said. “I find it to be very interesting when we come up with questions that don’t seem able to be answered in quantitative ways at the beginning – but at the end, we figure out some ways (to find answers) which are quantitative, and we can verify the results. That’s the place where we find wonder.”

Linking the analytical skills to a more relatable topic such as love made the course feel less daunting to Ronaa Ayesha Kong, a first-year chemistry major. “In other statistics modules, every lesson seemed so boring and dry, and I would get really stressed out studying for the tests because I didn’t really understand the concepts and there was nothing that I could relate it back to,” she said. “But when you study something that you like and you want to know more about, it changes the game completely.”

Second-year business major Joanne Hu appreciated getting to pick a project topic, rather than just solving pre-set questions and finding trends in data. Her project group chose to study a purported relationship theory they came across on TikTok, and the process of gathering and analysing fresh data for the relatively unexplored question boosted her confidence in applying the skills she had learnt.

“Statistics can be quite boring if it’s not put in the context of something interesting. I have seen friends taking pure statistics modules struggling a bit because it’s quite theoretical,” Joanne said. “For our module, I think many people had fun analysing a topic that we enjoy. The framework of searching for a romantic relationship makes it less dry.”

This story first appeared in NUSNews on 21 June 2024.