Beyond Sushi and Umami: Curating an Immersive Experience through Japan’s Culinary Culture

May 4, 2023

IN BRIEF | 8 min read

- Find out how Associate Professor Emi Morita and Associate Professor Hendrik Meyer-Ohle from the Department of Japanese Studies curate an immersive, experiential pedagogical experience that brings to life the politics, culture, history and religion of Japan through the lens of culinary culture.

At the start of every term, Associate Professor Emi Morita, from the Department of Japanese Studies at the NUS Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, asks students to name their favourite Japanese food. Sushi and ramen are usually the top contenders.

What many of her students do not realise is that these two dishes originated outside Japan.

Sushi, for example, traces its origins to the paddy fields of Southeast Asia, where people tried to ferment and preserve fish using rice. And ramen, which comes from China, became more popular in Japan after World War II, when the country faced a food shortage and received large quantities of wheat from the United States.

“What they think is Japanese food has very complex histories,” said Assoc Prof Morita. “We cannot ignore such histories of culture, politics, business, and international relations.”

Her module, titled Itadakimasu – Food in Japan, has been running at NUS for the past 11 years. And of course, there is no better way to appreciate the complex history of Japanese culture than to get an actual taste of it.

That is why a Japanese tea ceremony (sado) – where students get to partake in the ceremony led by instructors from Japan – has long been a highlight of the course, which emphasises immersive experiential learning that takes education beyond the classroom.

There is meaning and intent behind every step of the ritual – from the way people sit on tatami mats to the orientation of tea bowls and the exchange of bows. The decorations in the room, and the types of sweets served, reflect the time of year. Every tea master, dressed in traditional kimono, serves matcha sourced from their favourite tea farm in Japan.

“Because it has a lot of Zen Buddhist elements, the tea ceremony is not really explicitly – or verbally – taught, I don’t want to explain it too much during the tutorial, because the students should feel something themselves by experiencing it,” said Assoc Prof Morita, who added that the 45-minute session, held in the university’s Japanese Studies Culture Room, consists of a heavily-abridged version of the full ceremony, followed by class discussion.

“There is a certain way to pick up the utensils, and what to say, and how to bow. I emphasise (that they should think about) why there are such prescribed rules. For example, the (right) way to pick up chopsticks or pick up the tea bowl minimises the chance of damaging the precious object. And knowing how to bow, what to say, is about showing respect to others.

“You situate yourself in the nexus of the social network, and think that you are here but you are also aware of the other people. You are here because other people are also here.”

To see the World in a Grain of Rice

Assoc Prof Morita and her department colleague, Associate Professor Hendrik Meyer-Ohle, have helmed the Itadakimasu – Food in Japan module from day one. Itadakimasu, which means “I humbly receive”, is commonly said before the start of a meal in Japan.

While the two professors are the course coordinators, most of the classes are run by guest lecturers from different disciplines who share their insights on Japanese politics, religion, culture, and society through the lens of food.

“You cannot really understand food culture,” said Assoc Prof Morita, “unless you look into history, politics and religion.”

“We wanted to create a larger image of Japan, and food was a vehicle to do that,” added Assoc Prof Meyer-Ohle. “We are one of the larger Japanese departments in the world, especially in terms of the breadth of colleagues – (among whom are) historians (and researchers of) popular culture, business, politics, and society.”

Both professors have lived in Singapore for about two decades. Assoc Prof Morita, an applied linguist from Tokyo, has an especially deep affinity with food – her family runs a 75-year-old restaurant near Shinagawa selling “home-style” Japanese dishes. Assoc Prof Meyer-Ohle, who comes from the northwest German city of Osnabruck, wrote a PhD thesis on the introduction of supermarkets, convenience stores and modern retail formats to Japan.

Savouring the Taste of Umami

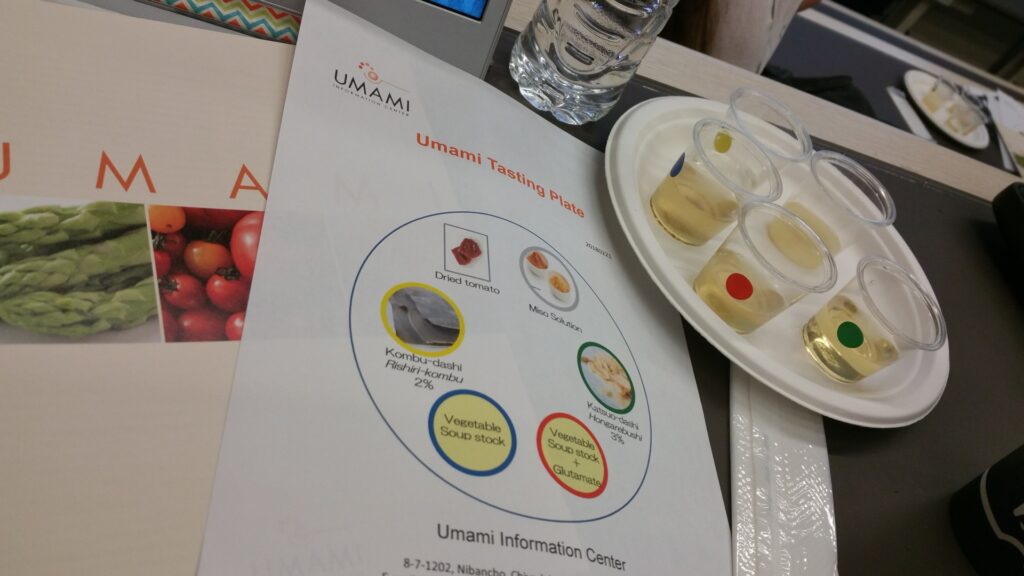

Another hands-on feature of the course is a tasting session by monosodium glutamate (MSG) producer Ajinomoto. Students take part in a “chemistry experiment” where they mix solutions consisting of bonito (a type of fish) and kombu (kelp) to create the flavour of umami, or a uniquely Japanese savouriness.

Assoc Prof Meyer-Ohle shares that students are encouraged to think critically about issues such as the “MSG debate” which includes criticisms that the popular flavour enhancer is bad for health.

Claims about its negative health effects date back to a letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1968 from a physician who suggested that the food he ate at Chinese restaurants led to symptoms such as headaches and heart palpitations, coining the term ‘Chinese Restaurant Syndrome’.

Subsequent studies, however, have failed to show a clear link between these adverse reactions and the flavour enhancer, and the US Food and Drug Administration considers MSG-seasoned foods to be “generally recognised as safe”. The term has since been criticised for being pejorative and unscientific.

Such negative perceptions were “partially motivated by anti-Asian sentiment at the time,” said Assoc Prof Morita. “What I emphasise during the lecture is that if you hear some kind of statement, you should always check who is saying it, and what is the political motivation behind it.”

Besides tutorials, hands-on activities and readings, students also get the opportunity to engage in a debate on the controversial topic of whaling, challenging them to spar intellectually about real-life issues. They also have to write a reflective essay on their takeaways from the tea ceremony.

“The course material is very fun, but that doesn’t mean it’s an ‘easy’ course,” noted third-year undergraduate Isabelle Metzger, who is majoring in Political Science. “The topics are very structured and very insightful. It has that academic rigour to it.”

To fellow student Irfan B. Ibrahim, a third-year Psychology major, the tea ceremony was a highlight of the course.

“What it is trying to do is pull you away from the mundane, into the ritualistic realm,” he observed. “The concept is about ichigo ichie, which means one meeting, one occasion: you should really cherish the moments you experience, because you never know when you’ll get a chance of having it again.”

He added: “It’s a very enriching module. You don’t just learn about food. You learn about life, about yourself, and even your own culture.”